HALIFAX -- For more than 30 years, Ricky Hallett has fished the rich waters of Jordan Bay on Nova Scotia's seafaring south coast.

From his doorstep on a perch above the bay, he can look out to the harbour that has spawned the lobsters that have provided for his family for generations.

But the 52-year-old fisherman says he fears that could change in the coming years after a New Brunswick company was granted approval this week to set up open-net fish farming pens in the bay -- an estuary that is a breeding ground for lobsters.

"I'm worried about my livelihood, I'm worried about the ecology of the harbour and I'm worried about the future of lobster reproduction," he said from his home in West Green Harbour.

"Do you ever see a maternity ward in a cesspool?"

The language may be dramatic, but it fits with an increasingly polarized debate in the province between people in traditional fisheries, the NDP government and aquaculture companies interested in expansion.

At the heart of the dispute are so-called open-net pens used primarily to raise salmon and trout in waters along the Nova Scotia coast, with sites stretching from Cape Breton to Digby.

There are 31 finfish sites in the province that are in current or planned production along with two in the application process.

The province recently released its aquaculture strategy that emphasized expanding the industry to boost jobs in parts of rural Nova Scotia hit hard by unemployment and outmigration.

But the push by the NDP to increase the number of open-pen sites has generated opposition from both citizens' groups, who insist they foul the environment, and fishermen like Hallett, who fear they will harm the lobsters and imperil their livelihoods.

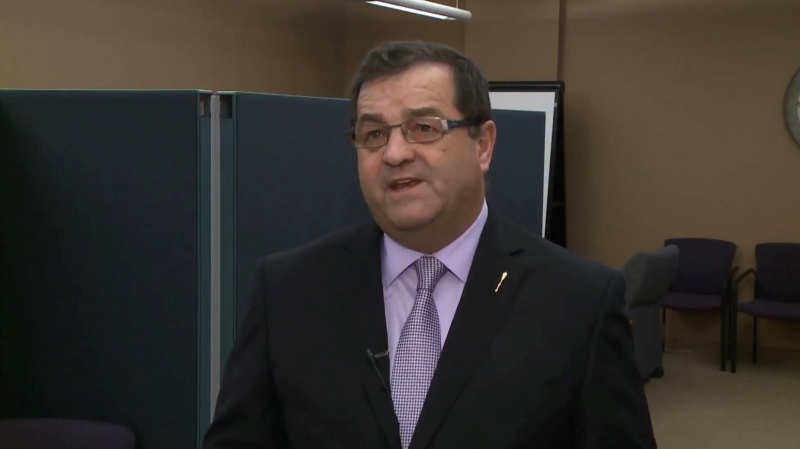

Fisheries and Aquaculture Minister Sterling Belliveau says he appreciates the concerns, having been a lobster fisherman for 38 years in the riding of Shelburne -- one of the province's aquaculture hotbeds.

But he insists that any expansion of the industry won't be done at the expense of the environment or the centuries-old traditional fisheries that are worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year and support dozens of coastal communities.

"I'm confident that we are showing a blueprint of a path forward in a bright future for rural Nova Scotia," Belliveau said in an interview.

"I am confident that nobody's going to have harm or do harm to the environment and we are committed to a monitoring process and that this industry is done right."

The province's aquaculture industry is worth about $50 million a year, with the marine-based pens making up more than half of that. In its strategy, the government says it wants to triple that business, through new processing operations and increased employment.

However, some scientists and ecologists say the province should tread carefully and look to other jurisdictions that are grappling with problems linked to the ocean farms and consider curtailing expansion.

The Cohen Commission that looked into the decline of sockeye salmon in British Columbia recently recommended a freeze on net-pen salmon farm production in the Discovery Islands until 2020.

It said the federal Fisheries Department should prohibit all such salmon farms in the area if it "cannot confidently say the risk of serious harm to wild stocks is minimal."

Jeff Hutchings, a marine biologist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, says high-density pens pose multiple threats to the environment because they can deposit so much waste in a small, concentrated area.

Hutchings, who chaired an expert panel on climate change and marine biodiversity, said the waste includes fecal matter, feed and chemicals that treat sea lice infestations associated with salmon.

"One needs to weigh the purported benefits against the costs -- a few jobs might be at the cost of the marine environment," he said. "These are problems that have been demonstrated elsewhere."

Escaped fish from salmon farms have been found in rivers in Atlantic Canada, raising the risk they will breed with wild salmon and alter the genetic makeup of the fish, he said.

Disease can also spread quickly in the pens, he said, citing the outbreak of infectious salmon anemia in New Brunswick, which led to mass culls in the 1990s, millions in losses and federal compensation worth tens of millions.

Last April, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency ordered Cooke Aquaculture to destroy salmon in their ocean pens outside Shelburne Harbour due to the presence of the virus.

In an email, the agency said it confirmed anemia at four commercial, but unnamed aquaculture facilities in Nova Scotia, with two still under quarantine.

Nell Halse, a spokeswoman for Cooke Aquaculture, said the company has been operating in Nova Scotia for 15 years and is well aware of the opposition. But Halse says there is no proof the farms have harmed lobster populations in New Brunswick, which has had aquaculture operations for 30 years.

"The concerns that they raise are not new to us. They're serious concerns that we take very seriously," she said. "But there is not any evidence that our industry has had a negative impact on the lobster fishery in New Brunswick."

Despite that, Hutchings said the province should be investing in more research before granting approval for more open-net pens.

"The province needs to beef up its science and undertake independent risk assessments and provide incentives for closed containment, on-land facilities," he said.

"Canada's a bit behind the times in terms of evaluating the risk."

Opposition Liberal Leader Stephen McNeil agrees, saying the NDP has failed to put adequate regulations in place before allowing further aquaculture expansion.

McNeil says he is not against the practice, but argues that the government needs to determine how many fish and pens can be in a certain area, the number of jobs they will create and if there are areas that are not suitable for the pens.

"We're trying to close the barn door here while the horse has gotten out," he said. "This government has jumped into the open-net pen aquaculture industry without fully understanding it and fully putting in rules and regulations that are going to be there to govern it.

"We've bought in."

Belliveau, who is also the environment minister, dismisses the criticism, saying regulations are in place and the government has proceeded slowly, only approving three new sites since taking power in 2009.

"We have over 13,000 kilometres of coastline and to me ... it's a very minor footprint," he says about the pens, adding that lobster landings are at historic levels in areas with open-pen fish farms.

"I know that there can be harmony."

Still, there could be a steep political price for the government, which both angered and pleased people when it announced in June that it would lend Cooke Aquaculture $25 million to expand its operations in Shelburne, Digby and Truro in an effort to create more than 400 jobs.

For Hallett, the debate has created a rift in his hometown between people eager for promised employment and some fishermen. And he insists it will be felt at the polls.

"It sort of polarizes communities -- you divide a small community and pit neighbour against neighbour or brother against brother," he said.

"I voted for change last time around and I voted for change that was bad and I will not make that same mistake again. They've lost me and they've lost a lot more people provincially."