Bat populations have plummeted in the Maritimes over the last three years, thanks to a fungus called white nose syndrome.

The fungus began killing bats in New York in 2006. It arrived in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in 2011.

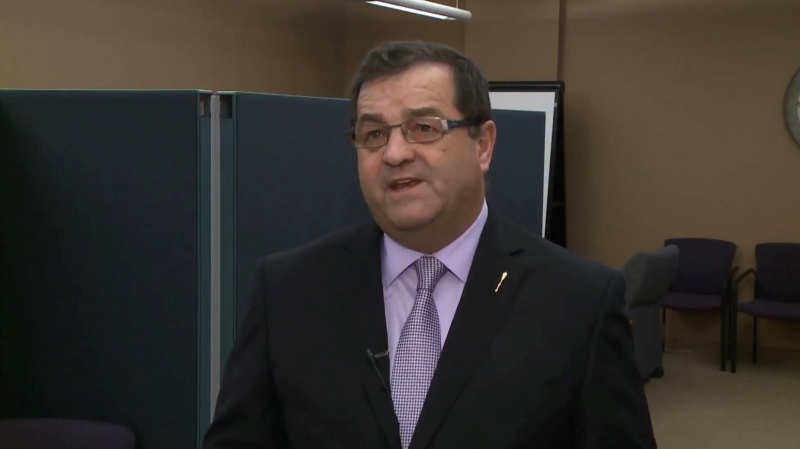

Mark Elderkin, an endangered species biologist with the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, says healthy populations of bats could be found in many areas three years ago.

Since 2011, he has watched 98 per cent of the population on mainland Nova Scotia disappear.

“There's never been seen such a massive decline of any mammalian group,” says Elderkin.

“Actually, that's consistent with what Dr. Don McAlpine has documented in New Brunswick as well; it's about 98 per cent.”

White nose syndrome has had an impact on bats in all three Maritime provinces and is getting worse. Cape Breton was the last unaffected area, but the disease was recently confirmed on the island.

“It will probably be another year or two before the disease manifests itself full blown to the level we've seen here on the mainland and elsewhere,” says Elderkin.

Estimates show that bats save the U.S. economy billions of dollars each year by eliminating pests that destroy agricultural crops and trees essential to the forestry industry, and they have a similar impact in Canada.

Four species of bats are common in Nova Scotia and three are susceptible to white nose syndrome.

Elderkin says there is still a chance the endangered bats could survive, but it would take decades, or even centuries, for the population to return to the kind of numbers they were seeing before 2011.

In response, the Nova Scotia government has set up a bat conservation website, where people are encouraged to report sightings.

“What we're learning already from the public reporting tool is that there clearly are areas, for reasons totally unexplained, there are still bats. Now, how long that will last, or if it will last, we don't know,” says Elderkin. “We don't know if the bats that are surviving are actually immune to the disease, or whether it’s an acquired immunity over time. We don't know.”

Elderkin says public reporting is key to discovering patterns that may help bats recover in the future.

With files from CTV Atlantic's Jayson Baxter