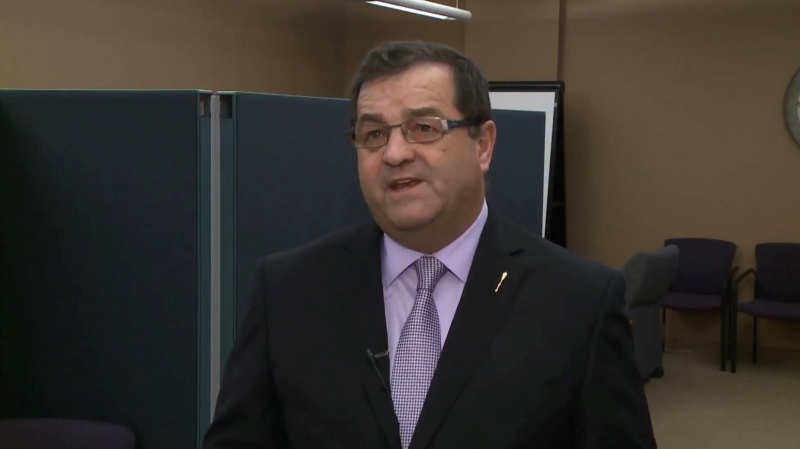

HALIFAX -- The 14-year delay in bringing accused sex offender Ernest Fenwick MacIntosh to trial was a miscarriage of justice, federal Justice Minister Peter MacKay said Friday as he released the findings of an internal review that points to human error and breakdowns in communication by both provincial and federal officials.

MacKay also apologized on behalf of the federal government, saying the institutional failures were such a disgrace that he was left shaken by the bureaucratic bungling.

"For the victims, the tragic impact on their lives of sexual abuse was compounded by systemic failure and human error," MacKay told a news conference in Halifax.

"Many decades have gone by since the time of the first accounts of abuse, and yet after all this time, Mr. MacIntosh has never had to account for the dozens of sexual assault charges against him. This is a horrible case showing justice delayed is justice denied."

In 1995, MacIntosh was living in India when he was first accused of sexually abusing boys in the 1970s. But the former Cape Breton businessman wasn't extradited until 2007 and his first of two trials in Nova Scotia didn't start until 2010.

In April of this year, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld a lower court ruling that quashed 17 sex offence convictions against him, saying it took too long for the case to come to trial.

"I wish to apologize and express my sincerest regret for the mistakes made by federal employees who played a role in this tragic case, and the institutional failures that contributed to the travesty," said MacKay.

"As a new father I am particularly horrified by these crimes against children. There's little in this world that I can imagine is more heinous or counter to Canadian values than the harming of an innocent child."

One of the complainants in the case said in an interview from his home in British Columbia that he doesn't accept MacKay's apology and wants a public inquiry where witnesses must speak under oath.

"I like Peter (MacKay), I think he's been the only politician who has done anything," said the complainant, whose identity is protected by a publication ban.

"But I don't accept their apology, no."

In May, MacIntosh sent a letter to the province's justice minister maintaining his innocence and saying he would welcome a public inquiry into the case so long as it went beyond looking into what caused the delays.

MacKay said Friday a public inquiry would not add to what has already been learned from the federal review, as well as previous reviews conducted by Nova Scotia's Public Prosecution Service and the RCMP.

"It would take an extraordinary amount of time and I suspect it would also be extremely costly," he added.

The latest review, which included investigating the role of the federal Immigration and Public Safety departments, concluded that in the context of a 10-year extradition process, federal Justice officials were responsible for an 11-month delay between 2003 and 2004.

MacKay highlighted the fact that the provinces are responsible for administering justice. In this case, he said, Nova Scotia's justice system failed.

"Nova Scotia has already admitted a lack of diligence on its part and shouldered much of the responsibility," he said.

Provincial Justice Minister Lean Diab, who was sworn in Tuesday to the new Liberal government's cabinet, said she was still reviewing the file and couldn't comment.

"My heart bleeds for the victims and it bleeds for the victims' families," she said. "We need to do everything in our powers ... to ensure that this does not happen again."

The federal review says provincial justice officials turned to Ottawa to begin the extradition process in 1997, but waited 15 months before providing some of the needed documentation.

There were more delays, and in April 2002 federal officials contacted their provincial counterparts to see if they needed help, the review says. Some of the required documents were forwarded in June 2003.

At that point, a problem arose at the federal level. A reassignment within the Justice Department's International Assistance Group led to the 11-month delay MacKay cited.

"The new counsel who received the file did not appreciate its urgent nature," the report says. "This was a mistake given the cumulative delays."

In the meantime, the province's Crown lawyers were still gathering evidence for a formal extradition request, a process that wasn't completed until May 2006.

An internal review by the Nova Scotia Justice Department found these delays were partly caused by the heavy workload facing a Crown attorney in Port Hawkesbury, N.S., and two unexplained passport renewals that allowed MacIntosh to stay in India for years before he was extradited.

MacIntosh's passport was renewed in 1997 and in 2002, despite the fact he faced outstanding charges and a warrant had been issued for his arrest.

The federal review says it remains unclear why MacIntosh's passport was renewed in 1997 even though his name was added to a watch list in 1996.

Federal officials confirmed they tried to revoke MacIntosh's passport when they learned of the mistake, but MacIntosh challenged their efforts in court. A federal judge later said he was concerned by a lack of documentation and that the Crown was trying to use the revocation process to further a police investigation.

To avoid a precedent-setting loss in court, federal officials decided to let MacIntosh keep his passport.

In 2002, MacIntosh's passport was renewed in New Delhi because the passport security division failed to make contact with the RCMP, the review says. The cause? "Human error."

The review concludes with a list of improvements that have been made to the extradition process and the passport system, including increased staffing and improved access to police files.