HALIFAX -- In the wind-blown sands of a narrow, crescent-shaped island off the coast of Nova Scotia, a Coke bottle from 1962 was found resting next a prescription bottle from 1861.

The juxtaposition is telling of Sable Island's unique and challenging characteristics, said Parks Canada archeologist Charles Burke.

Burke said wind erosion has entombed many artifacts and structures on the sandy island -- a National Park Reserve -- and has scoured clean thousands of others, leaving them in plain sight.

"Usually an archeologist has to dig to get information. In this case, there's no digging required. All the artifacts are scattered on the surface," said Burke. "It was completely unlike anything I've done in 40 years of archeology."

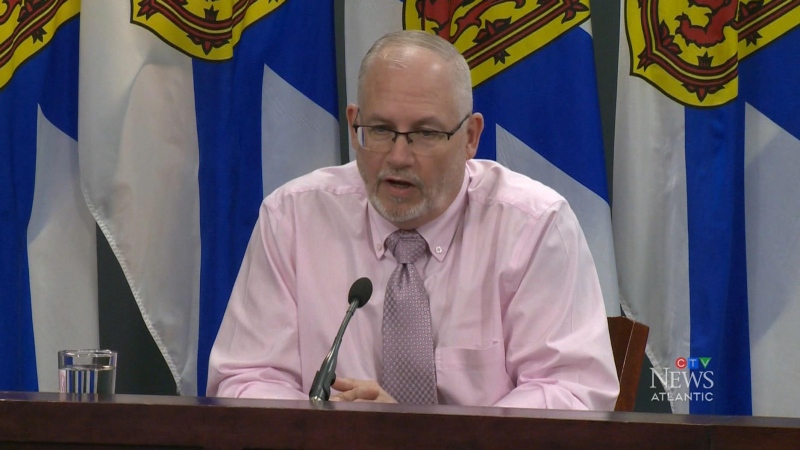

Burke conducted the island's first-ever systematic archeological survey in August 2015 and will share his findings on Tuesday during a lecture for the Nova Scotia Archeological Society.

The island, which sits roughly 300 kilometres southeast of Halifax in the Atlantic Ocean, was once inhabited by life-saving crews who rescued and recovered ship wrecks during the mid-20th to mid-21st century.

More than 350 vessels have been wrecked due to the rough seas, fog and submerged sandbars surrounding the island, earning it the title "Graveyard of the Atlantic".

Evidence of those early occupants -- everything from pots, pans and toiletries to stoves, bathtubs and horseshoes -- are sprinkled around the 42-kilometre long island, said Burke.

But new evidence uncovered during the survey reveals that humans lived on the island as early as the mid-1700s, said Burke.

"That's a 100-year period -- 1750 to 1850 -- for which we have no knowledge currently as to why there was a structure there or people living in that area," said Burke. "This is new information and it's going to require additional research."

The island, known for its population of feral horses, is essentially a giant sandbar. Burke said the artifacts he found were once buried beneath the sand, but wind erosion has brought them to the surface.

Burke said that presents a challenge, as normally archeologists can date items by how deep they are buried in the ground. He said the wind also acts as a "sand blaster," which has removed many identifying markings or labels from items.

"The difference at Sable is that there has been no human disturbance. There have been no machinery or shovels moving things around. The wind is the primary culprit and it has removed all the strata so now we have the old and new side-by-side," said Burke.

"This is a unique aspect of Sable Island and frankly it's a real challenge to make sense of it."

He said more research will need to be done to find out about the artifacts and paint a broader picture of the history of Sable Island.

The wind is also to blame for destroying some of the island's structures. A house near the location of the eastern life-saving station that was still standing in the early 1960s is now a pile of splintered wood, said Burke.

But the wind is also responsible for preserving structures. Another two-storey house is currently intact and completely buried in sand, he said.

"You don't have any opportunity to record the house because you can't see it anymore. It's now a sand dune," said Burke, adding he often had to wear goggles during his survey to protect his eyes from blowing sand.

"We've already established through mapping and air photos where the house is located, so we can at least now be prepared for when the wind erosion begins to expose that house again."

Burke said the data collected will allow Parks Canada to map areas that were occupied by humans and establish monitoring protocols to measure the impact of wind erosion and site exposure.