One of the most frequently asked questions I get this time of the year is “will we have a white Christmas?” As a meteorologist I tend to work mostly within the next several days, so as we edge closer to Christmas Day, I’ll be able to put together a forecast for that. In the meantime, though, it had me thinking about what the historical odds were for a white Christmas in the Maritimes. That type of information jumps from weather and into climate, so who better to speak to about it than David Phillips, a senior climatologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

David Phillips has dug into the historical records back to the 1950s, when Canada began to keep track of snowfall and snow on the ground. He was looking for how often a location had two centimetres of snow on the ground on Dec. 25, which is the definition in Canada of a white Christmas. It doesn’t matter if that snow fell on Dec. 25 or last week, as long as two centimetres could be measured on the ground.

It’s no surprise that for the Maritime region the odds are highest for a white Christmas the further north and west you go -- a more continental climate -- with the odds falling as you get closer to the marine influence of the Atlantic Ocean waters. Historically, a location such as Bathurst has close to a 90 per cent chance of having a white Christmas. That number falls to 78 per cent for Charlottetown, 60 per cent for Saint John, and 54 per cent for Halifax. Those percentages are calculated from observations made from 1955 to 2017.

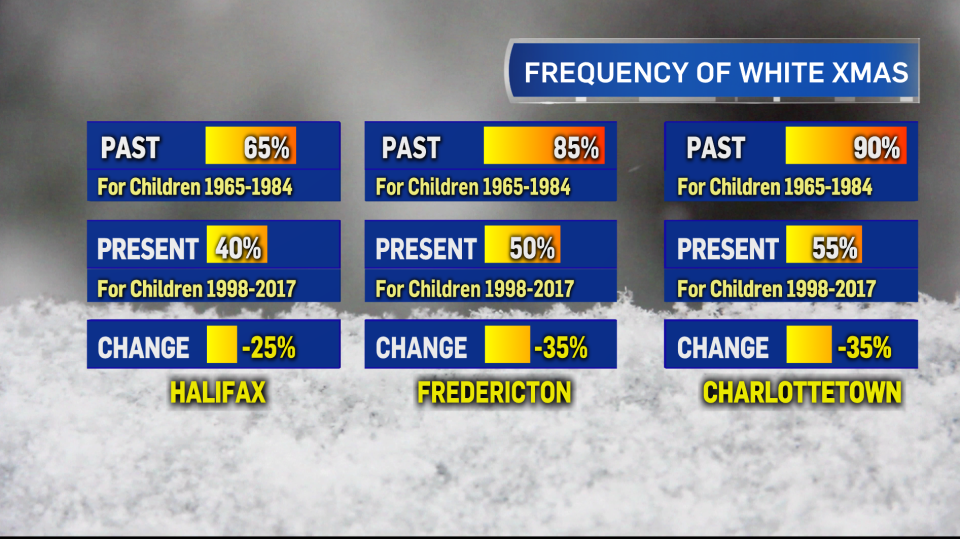

He also looked at how the frequency of a white Christmas has been changing over the years. To do this, he compared the statistics of a white Christmas for adults and children for a period from 1965 to 1984 to the statistics closer to the present, 1998-2017. While I was reviewing these numbers it stood out to me that some of the largest change in frequency of occurrence of a white Christmas in Canada was in the Maritimes. I asked him if there is a particular reason or reasons for this and, surprise, surprise, it turns out to be connected with changes in both the air temperature and ocean water temperature.

“In the 1950s, 60s and 70s, while Canadian winters were warming slightly, winters in Atlantic Canada were getting colder. Cold Atlantic water was chilling the air that much more. However, since the 1980s, Atlantic Canada has been catching up and warming faster than any region in southern Canada,” explains Phillips.

The trend towards warmer ocean water, and generally warmer temperatures in December, impacts how much snow falls and sticks around the region through early winter.

Now, within a long-term trend, there is going to be some variance from year-to-year. For example, the fall and early winter this year appear to be bucking the trend with some early season cold snaps across the region. For those hopeful of snow on the ground come Christmas Day, that is helping to improve the odds. This is especially true for those parts of the region that already have a decent snowpack down, which includes much of New Brunswick, parts of Prince Edward Island, and some areas of Nova Scotia (mostly in the north and east, away from the Atlantic coastline). Other than that it will be luck of the draw in seeing what weather systems move in closer to Dec. 25 and what type of precipitation and temperatures they will be packing.