HALIFAX -- Fred Turnbull was only 19 when his landing craft approached the beaches of Normandy as part of the greatest amphibious assault in military history.

Now 92, Turnbull, who was a Royal Canadian Navy bowman-gunner, said he still vividly remembers the confusion of the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944.

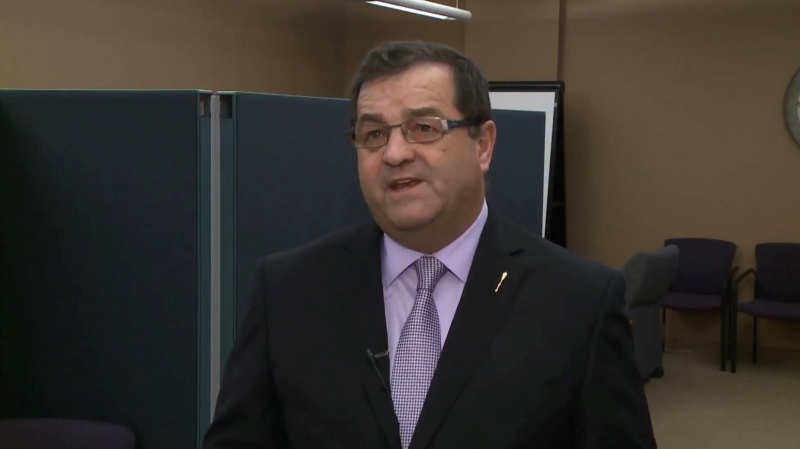

"From the air it must have looked like a mix-up of landing craft going in all directions," the retired banker said, moments after receiving France's highest decoration, the Legion of Honour, at a ceremony Friday at Canadian Forces Base Halifax.

"And I think probably the worst thing was the noise. The noise was terrible because we had our own battleships firing in and the Germans firing out."

Born in Montreal, Turnbull was just 17 when he joined the navy in the summer of 1942. Serving aboard landing craft, he took part in several Allied operations including landings in Sicily, Normandy, southern France and Greece.

His job was to drop the ramp of the landing craft and then jump over the bow to help steady it with a rope as the soldiers it carried disembarked and headed ashore.

It was a dangerous job with little protection from enemy snipers, mortars, aircraft and minefields. Turnbull said there was little time to be afraid.

"You just have a job to do and you do it," he said. "That's where the training comes in. You train so much, everything's automatic."

Turnbull was presented with his medal by Laurence Monmayrant, France's consul general for the Atlantic provinces. He is one of over 600 Canadian veterans who have been awarded the five-armed cross created by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802.

"You are a living page of the history of my home country," said Monmayrant. "Your contribution to its liberation needed to be recognized."

Monmayrant later said that meeting Turnbull and bestowing him with the award was a special honour for her.

"I come from Normandy and from a very early age we are told of the role of the soldiers who came from the U.S., from Canada ... who came to the rescue of France and Europe," she said.

Turnbull said he was proud to receive the honour, which he dedicated to his comrades in arms.

"I never thought that this would happen," he told a gathering of family, friends and military dignitaries.

"But I'd like to say this is on behalf of all the landing craft crews."

Turnbull recorded his wartime memories in a diary, which at the time was forbidden by Allied authorities. The diaries eventually formed the basis of a book that was published in 2007 entitled "The Invasion Diaries."

He said he hid the diary in his hammock and recorded his thoughts often a week to 10 days after certain events had unfolded.

"But then in the early 80s the government said all those who have diaries can deposit them in the national archives and get a tax benefit, so everything changed," Turnbull chuckled.

After the war, Turnbull studied history and economics at McGill University and eventually worked for Montreal Trust, retiring as an assistant vice president in 1989.

"I got into business and you sort of forget day-to-day what went on," he said. "Life goes on."