HALIFAX -- A Dartmouth, N.S. lab is making important progress in the global race to develop a vaccine for COVID-19.

So much so that it hopes to undertake its first round of human trials this summer.

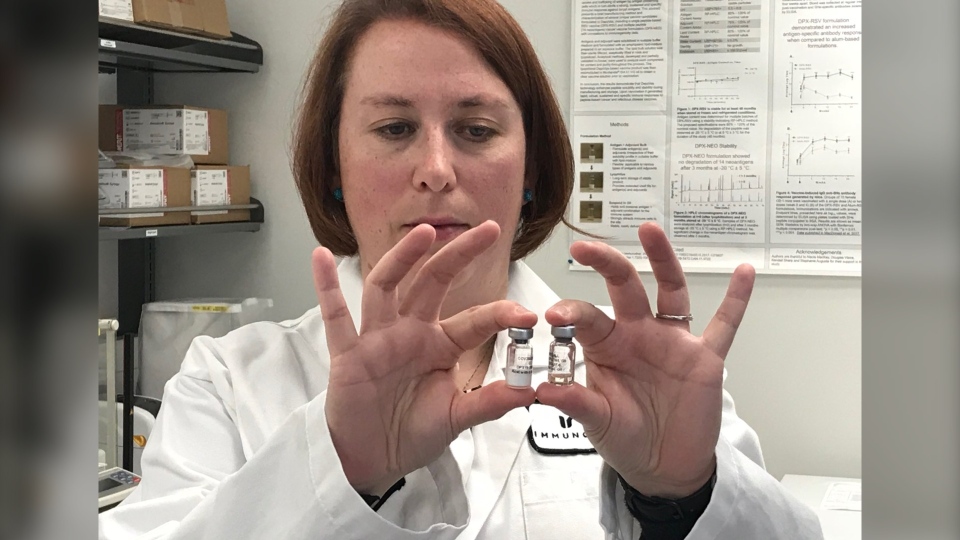

“This is what one of our vaccines would look like,” says Marianne Stanford, vice-president of research and development at IMV, while holding vials filled with components of what could be a vaccine for COVID-19 during CTV News' exclusive look inside the Dartmouth lab.

One vial holds the powered vaccine, which would then be mixed with the company’s unique oil-based delivery system to be injected into the body.

Drug companies and scientists all over the world are involved in the search for a vaccine, with at least five candidate vaccines in clinical evaluation and another 71 in clinical preclinical evaluation, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

IMV is a biopharmaceutical company with staff in both Dartmouth and Quebec City. It’s most known for its work developing a treatment for advanced-stage ovarian cancer. Last year, it also completed initial human trials in a vaccine for a serious illness caused by the respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. The illness hits infants and the elderly particularly hard.

Stanford says IMV’s work in that area meant her team was uniquely positioned to start on a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as the virus’ genomic sequence was made available to researchers at the end of February.

“Ninety per cent of what the company is doing right now is on SARS-COV2 and COVID-19," she says.

“When it became obvious that the most impacted population [by COVID-19] were the elderly, our RSV candidate [vaccine] was tested in older adults, and so the ability to do some immunoresponses in that population, was really important.”

The lab has had to make some adjustments to how it operates because of the ongoing pandemic, even though it has been declared an essential service by the government of Nova Scotia.

IMV staff who don’t have to be in the lab are working off-site. The company is also doing extra training to ensure there is no time lost to illness.

But the company says its singular focus on developing a vaccine means work that would have normally taken the lab six months has been completed in about six weeks.

With time ticking away in the fight against the new coronavirus, the IMV team began its first tests on laboratory mice last week.

“We’ll be taking a small amount of blood from the mice, and be testing them for antibody responses,” explains Stanford.

“The IMV vaccine is farther along than folks that are starting from scratch," adds Dr. Joanne Langley of the Canadian Centre for Vaccinology.

The IMV project is one of a number of projects underway in collaboration with the Canadian Centre for Vaccinology and the Canadian Immunization Research Network.

The hope is to start the first round of human testing of IMV’s vaccine this summer.

“Those small studies are usually done in 40, 50, or 60 people,” explains Langley. “Then there’s another step where you try it in larger populations and then you look to see if it works.”

The company says it has designed a trial that would require 48 healthy volunteers and it is preparing to make its application for the trial to Health Canada.

There would still be plenty of safety and regulatory approvals needed, but the company is optimistic.

“It’s really been a global effort,” says Stanford. “When you have that many scientists and that many people geared towards a single goal, then it’s hard not to be hopeful.”