FREDERICTON - Fisheries groups and academics say federal government cuts to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans will put the fishery at risk.

Maria Recchia, executive director of the Fundy North Fishermen's Association in New Brunswick, said every government scientist who has worked on the impact of aquaculture pesticides on the marine ecosystem and the fishery are slated to be laid off or transferred.

"It's very frightening to even have pesticides in the marine environment, but then to not have any scientists around to be studying it -- that's a whole lot more scary," she said Monday.

"If our fishermen discover a lobster kill tomorrow, who will study how they died? Will fishermen have to pay private scientists to do this work?"

The federal government announced last week it would cut the department's operational budget by $79.3 million over three years. It will mean a cut of about 400 people from its workforce.

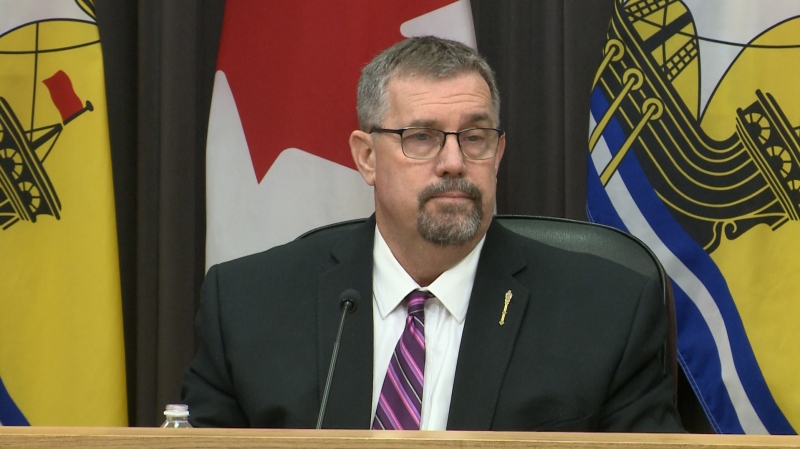

Fisheries and Oceans Minister Keith Ashfield was unavailable for interview Monday, but his spokeswoman, Erin Filliter, defended the cuts and said research will still be done.

"Fisheries and Oceans Canada is refocusing its research on priority areas that directly support conservation and fisheries management," Filliter said in an email.

"In lieu of in-house research on the biological effects of contaminants and pesticides, the department will establish an advisory group and research fund of $1.4 million a year to work with academia and other independent facilities to get advice on priority issues and ensure departmental priorities are met."

Recchia panned that idea.

"I think it would be challenging to get unbiased research when it's very likely that the research is going to be funded by the industries that are being examined," she said.

It was also rejected by Peter Hodson, a biology professor at Queen's University in Kingston, Ont.

"Effectively there will be absolutely no capacity within Fisheries and Oceans to measure chemicals, let alone comment on them. That's pretty disturbing. That's throwing away a long history of research," he said.

Hodson and about 100 other academics, business leaders and government employees signed a letter that was sent to Prime Minister Stephen Harper on Monday asking him to reverse the cuts.

In the letter, they say that without first-class scientists, the federal government would be unable to respond to crises that could cripple vital fisheries.

"For example, the rapid and very effective response by scientists from DFO and the National Research Council to the shellfish crisis in P.E.I. in the late 1980s literally saved the lives of many Canadians, the viability of the East Coast shellfish industry, and Canada's international reputation as a source of high quality seafood," the letter reads.

Pam Parker of the Atlantic Fish Farmers Association said Fisheries Department scientists have done a lot to help her industry grow.

"Certainly our salmon enhancement program and hatchery program wouldn't be where they are, for the conservation side, without the work that DFO scientists have done," Parker said.

She said the aquaculture industry in the Bay of Fundy works within very strict boundaries developed by department scientists that take into account tidal action and underwater currents.

"These boundaries are not just arbitrary lines on a map, but they actually mean something."

Hodson said increased oil exploration in the Arctic and the possible export of oil sands through the West Coast makes the need for in-house scientific expertise more important than ever.

"It's not to say that we're going to lose the fish, but if we don't protect them, we could certainly do a hell of a lot of damage."