He doesn’t know when he was born, and therefore he doesn’t know how old he is, but he believes he was around four years old when he became a soldier.

“I was not young,” he says. “I was young by body and I was young by mind, but I was not young. I was well aware that I’m there to fight, so I thought of fighting.”

Today John Kon Kelei is a lawyer, a university instructor, and an advocate for children affected by war. He dedicates his time to speaking out about his experience as a child soldier in South Sudan.

“It is a matter of choice,” he tells me. “You keep quiet and maybe some other children will be victims by the fact that people are not aware of it, or you talk about it and maybe you will save some few.”

We are meeting just days after the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) secured the release of 3,000 child soldiers in South Sudan, one of the largest ever demobilizations of children. 280 have been released so far.

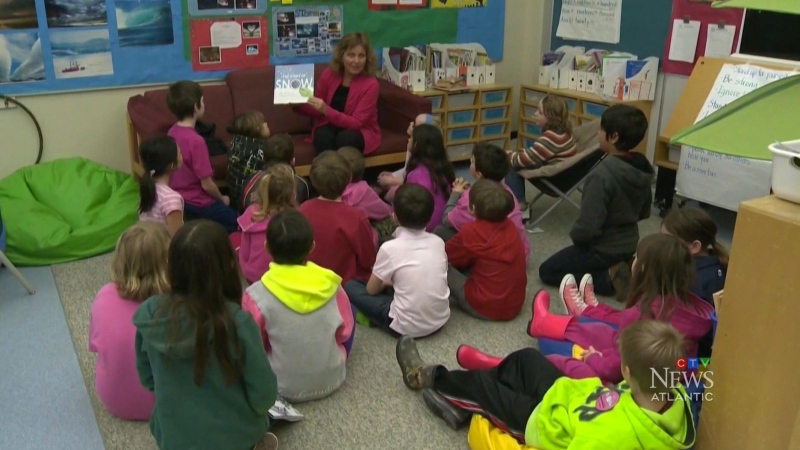

UNICEF has reached out to an organization in Halifax for help.

Kelei is not working with UNICEF but he has been to Halifax several times to work with the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative at Dalhousie University.

“I’m fond of that program,” he says. “That’s why I joined my hand with them, to at least raise awareness around the policy makers.”

Founded by retired Lt.-Gen. Romeo Dallaire in 2007, the Dallaire Initiative aims to eradicate the use of child soldiers worldwide.

Executive Director Shelly Whitman says people like Kelei give reality to the work they do.

“Asking children who were recruited if the interventions we propose would have made a difference,” she says via email from Halifax. “If they endorse your work then that is a million times more worthy than any donor or government's thoughts on the value of your work.”

Both Whitman and Kelei say it is always good news to hear of the release of child soldiers, but they caution there is much more work to be done.

“When you leave the military barracks that is the only thing you know, and that’s the only skill that you have to survive,” says Kelei. “But then you are sent to a civilian world which is totally new for you…I have always been complaining within the UNICEF itself to please stop with the short-sighted programs of rehabilitation and reintegration.”

UNICEF says this latest program will mean at least two years of constant work with the children, more if necessary depending on the child’s individual needs.

“It is significant to have this release of 3,000,” says Whitman. “But the worry is that each time South Sudan goes back to war children get used again, and we need to break this pattern.”

Whitman, who will be travelling to Uganda from Halifax later this month, is now hoping to also visit South Sudan. UNICEF wants to distribute the Dallaire Initiative’s handbooks here.

John Kon Kelei was not released from the army. After five years, he defected.

“If you don’t do it well and you are caught, you can wind up before the firing squad, so it is very dangerous,” he says. “It could mean death.”

Kelei urges people not to dismiss former child soldiers.

“People always think that these are children that went through the war, they can never achieve something higher. No, that’s wrong. Because if I could be the holder of a Master’s degree today, why not they?”

When the release secured by UNICEF is complete, there will still be an estimated 9,000 child soldiers in this war torn country. John Kon Kelei stresses the continued need for organizations like the Dallaire Initiative.

“To my friends in Canada, in Nova Scotia as a whole, please support this initiative. It is about the lives of some children. You can see me now, nice in suit, in a red tie. Many of the children are there outside, who may be much more beautiful in suits than I am, and they need your support.”

A plea from a man, who knows the realities of war no child should ever see.