Liberal politicians from the Maritime region are in Fort McMurray this weekend, taking part in a fact-finding tour to see how Maritimers are faring in the oil patch.

One concern they hope to address is what sort of impact working out west has on the workers’ families back home.

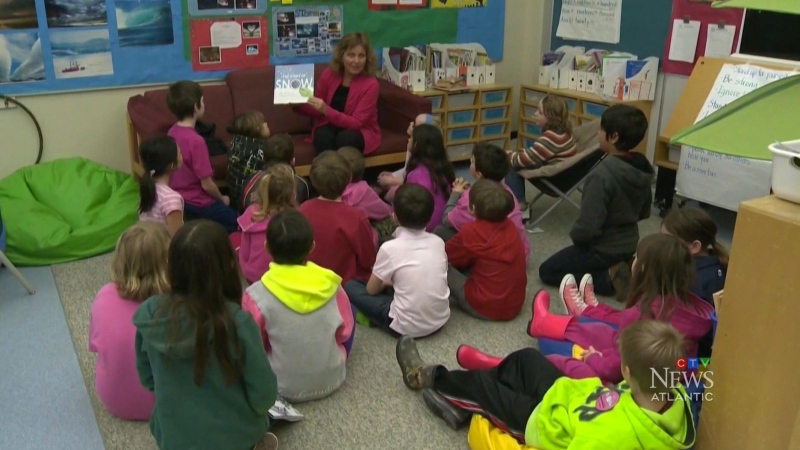

Jillian MacDonald’s husband Allan works as a driller in the oil patch.

He spends about two weeks on the job and then flies home for a two-week visit in New Waterford, making MacDonald a part-time single parent half of the time.

“He misses birthdays and other holidays, so that is kind of upsetting,” she says. “But this year he will be home for Christmas. Last year he wasn’t.”

While it may seem like anything but a normal way of life, it has become so for four-year-old Macy, whose dad has been commuting to and from Alberta since she was born.

“She gets a little bit confused,” says MacDonald. “But she knows when he is coming home and how long he is going to be home for, so it’s fine for her.”

In an area where the official unemployment rate tops 16 per cent, it is easy to understand the main reason for the endless westward migration.

A local employment resource centre would prefer to help those who are unemployed find work in their own communities, but the stark reality is that hundreds of Cape Bretoners, especially tradespeople, have little choice but to head to the oil patch, where home is often an isolated camp.

“You work; you go home back to your trailer. You eat and sleep. Then you do it all over again the next day,” says employment centre manager Tammy Marshe.

Like many oil patch wives, Jillian MacDonald is optimistic the local economy will rebound and her husband will no longer have to leave the province for a paycheque.

“Hopefully he will be able to move home and find employment some day.”

With files from CTV Atlantic's Randy MacDonald