INDIAN BROOK, N.S. -- It's been eight years since the body of Tanya Brooks was discovered in the basement window well of a Halifax school.

The murder of the 36-year-old mother of five from Millbrook First Nation remains unsolved, one of an untold number of cases of violence against Indigenous women and girls that a national inquiry will examine as it visits communities across the country this fall.

"My sister is one of the murdered Indigenous women in this country and I don't want her death to be in vain," said Vanessa Brooks, who plans on sharing the story of her sister's death with the inquiry when it comes to Nova Scotia in late October.

"One murder is one murder too many. We need to know why our numbers are so high, why our girls are going missing and why they're being murdered," she said. "We need this inquiry and we need answers."

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry has been embroiled in controversy and faces numerous criticisms, including failing to provide sufficient support to families.

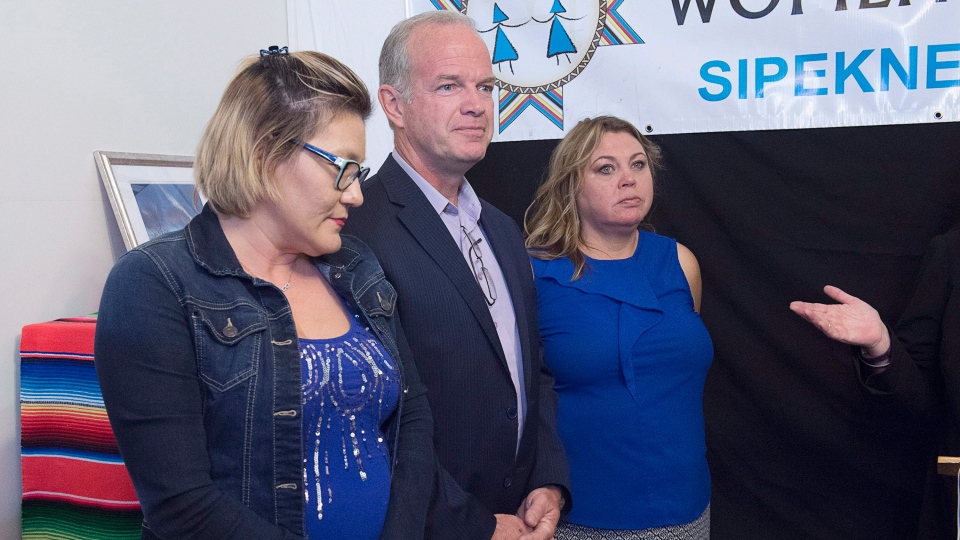

In an attempt to help families and communities through the process, the Nova Scotia government announced Thursday it has hired three community support workers.

Justice Minister Mark Furey said the outreach workers will support Indigenous women and families as they share their traumatic stories with the inquiry.

The positions are funded through a three-year, $790,000 agreement with the federal government.

In addition to supporting and counselling families and providing cultural support through smudging, prayers and sweat lodges, the unit of three outreach workers will share updates and information about the inquiry process.

Nova Scotia Native Women's Association president Cheryl Maloney said providing culturally appropriate services for Indigenous communities is "long overdue" and should continue beyond the inquiry's time frame.

"This unit is one of those things that should have been done years ago, not just for the inquiry but for justice for Indigenous women," she said. "There are things we can do now, that can be done better. We don't have to wait."

Marie Sack, co-ordinator of the new unit and a community support worker, said the team is already out in the field visiting Indigenous communities in Nova Scotia.

"It's a very delicate situation. Sometimes families don't want to even hear about the inquiry," she said. "They don't want to go back to a place in their life that they shut down and closed. But so far we've been accepted and listened to by families."

Sack said the team is reaching out to families to explain the inquiry and to see if they want to participate and share their stories.

"We're trying to get families to come forward to the inquiry to give their statements privately or publicly. We're preparing families and offering them the support or healing they may need."

The inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women is moving forward despite calls from some groups for a restart.

The inquiry is examining the systemic issues behind the high number of Indigenous women who have been killed or disappeared over the last four decades. It is expected to take two years and cost almost $54 million.

The first formal public hearing was held in Whitehorse in May, but subsequent hearings were pushed back until the fall.