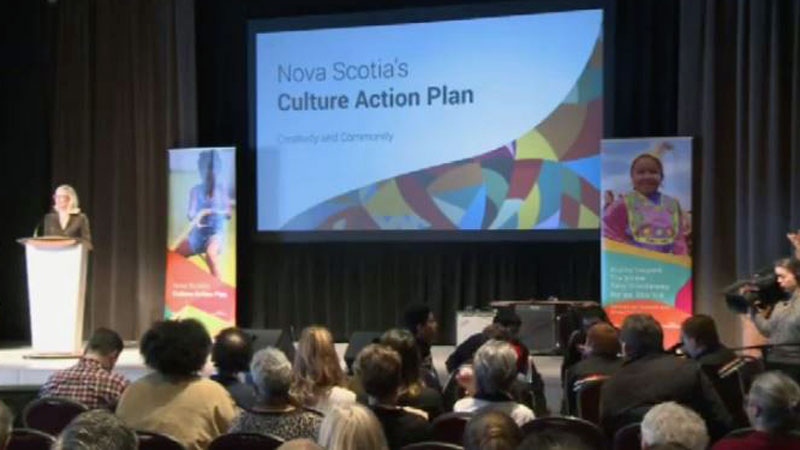

HALIFAX -- Nova Scotia is making a shift away from the traditional, tartan-centric notions about its culture.

There were no bagpipes, Highland flings or fiddles of any kind Wednesday when the government unveiled its first comprehensive plan to promote the province's culture and creative economy.

Instead, the event at the Canadian Immigration Museum on the Halifax waterfront featured traditional drumming from a group of Mi'kmaq youths, bhangra dancing performed by three Sikh men and videos featuring interviews with Syrian refugees and other immigrants.

As for the 29-page document, it places a heavy emphasis on promoting aboriginal culture and bolstering the province's "diverse communities," including its African Nova Scotian minority.

Despite Nova Scotia's strong historic links to Scotland, based on waves of immigration in the late 1700s, the word Celtic doesn't appear in the report -- though there is a nod to strengthening the province's office of Gaelic affairs.

Premier Stephen McNeil started his speech by suggesting Canada's second-smallest province has benefited from the recent arrival of Syrian families, whose children always seem to be "excited by the possibilities" that come with moving to a new land.

McNeil, who mentioned his Acadian mother and Scottish father, then focused his attention on Nova Scotia's "founding people," the Mi'kmaq. He said the province's largest aboriginal group has for 400 years provided newcomers with a warm welcome and has been open to all cultures.

"They gave us a blueprint on how this province should be: inclusive, welcoming and celebrating diversity," he said.

The premier acknowledged some in the province, including the Mi'kmaq and the African Nova Scotian community, have seen their cultures ignored and harmed.

"Not everyone's experience over those 400 years have been positive," he said. "But I can tell you ... I want every Nova Scotian to see themselves in this plan, and to see themselves in this province."

Mi'kmaq Chief Wilbert Marshall, head of heritage and archaeology for the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq Chiefs, said the province worked hard to recognize the cultural contributions of his people.

"Before, as a government, it was, 'We'll shove it down your throat,"' he told the crowd. "Here, we had our own voice.

"It is our words ... I'm very proud of that."

Howard Ramos, a sociology professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax, said it's important to remember that the province's ties to Celtic and Gaelic culture remain strong.

"Let's not forget that the province is called Nova Scotia," he said. "The Gaelic history is not going to be lost as long as the province has that name."

McNeil himself rejected the suggestion that the province is shedding its time-honoured cultural touchstones.

"It's not at all a shift away from that," he said afterwards, mentioning the province's commitment to invest more in the music industry. "That's still part of our history. It's part of who we are. It's part of our culture."

Ramos said McNeil's suggestion that the province has much to learn from the Mi'kmaq makes perfect sense at this point in Nova Scotia's history.

"Much can be learned from that attitude toward diversity and difference, as we become a province that is welcoming to different people and cultures from around the world," he said.

"We can embrace that we had a significant group of migrants who came from Scotland and who spoke Gaelic well into the 20th century. However, tartans and that culture is not the only thing that defines Nova Scotia ... We are making room for so many peoples' histories that haven't been part of that narrative."