HALIFAX -- The Transportation Safety Board of Canada says it could find no safety deficiencies after investigating the capsizing last month of a Nova Scotia fishing boat that claimed five lives.

The independent agency said Monday it won't be issuing a report or recommendations to improve safety because very little could have been done to protect the 13-metre boat from a fierce storm that unleashed 10-metre waves and hurricane-force winds.

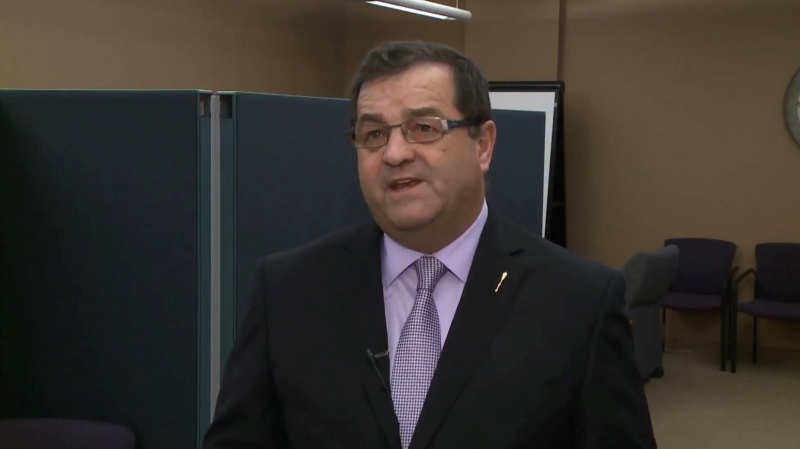

"It would be easy to say fishing boats shouldn't go fishing in the winter, but that doesn't make operational sense," said regional manager Pierre Murray.

"There's nothing you could do that makes sense that would prevent that from happening."

The Miss Ally, based in Woods Harbour, N.S., was on an extended trip to catch halibut off southwestern Nova Scotia when its emergency locator beacon transmitted a distress call via satellite late on Feb. 17.

Only 15 minutes earlier, the crew had been in contact with relatives on shore, saying they were riding out the storm with no problems.

The boat's Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon is a device that is typically activated only when it hits salt water, suggesting the boat flipped with little warning.

In the days after the vessel went missing, local fishermen said fishing for halibut in February has become common as quotas have expanded and the price for the fish increases as the wintertime supply shrinks.

The boat's upturned hull was spotted early in the massive search that followed. But the bodies of the five young crew members were never found.

Murray said investigators gathered evidence showing the boat was carrying only 1,400 kilograms of halibut in holds designed to carry 9,000 kilograms.

The vessel was properly equipped with safety and communications gear, he said.

As well, the crew -- all of them from southwestern Nova Scotia -- was aware they would encounter heavy seas and powerful gusts as they made their way to Sambro, N.S., from an area about 120 kilometres southeast of Liverpool.

"Any boat that size in a storm that big could very well have the same problem," Murray said. "You can't really pin the problem to the design of the boat itself. ... If you're broad side (to the waves) in hurricane-force winds, you could run into problems."

Though the capsized vessel was still floating days after the search for survivors ended, Murray said there would have been no point in retrieving the hull because its wheelhouse and living quarters were torn off.

In such poor condition, the vessel couldn't be subjected to a stability assessment.

"How can you assess the stability of the boat if half the boat is gone?" he said. "We have no special concern about the stability of this vessel."

A Royal Canadian Navy ship equipped with a remotely operated underwater vehicle was used to inspect what remained of the Miss Ally.

Still, Murray said there are some questions that will forever remain unanswered.

For example, it remains unclear what happened in the moments before the boat capsized, including the possibility that it lost engine power and could not be steered into the swells, he said.