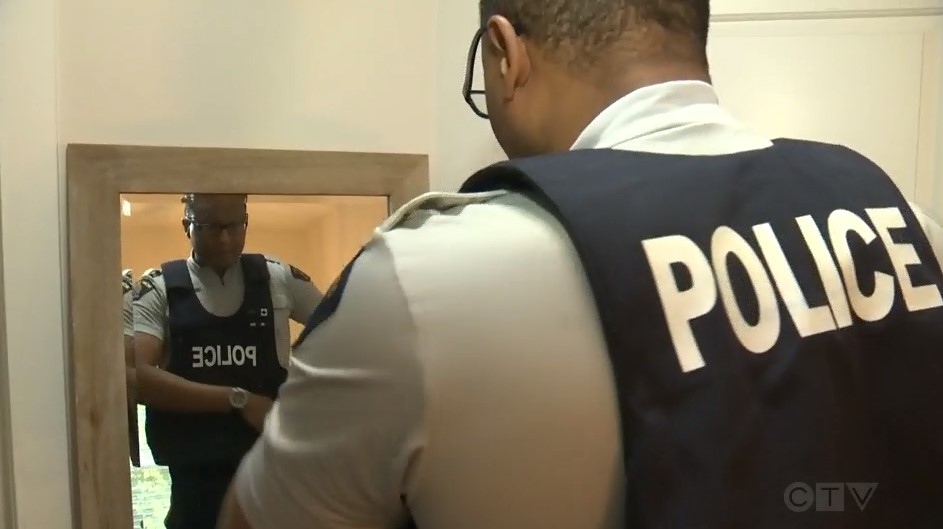

HALIFAX -- Const. Justin Simmonds is the first RCMP officer from North Preston, N.S., to be assigned to the community’s detachment.

Simmonds says it was a dream of his to come back and work where he grew up.

“It’s awesome. You’re driving around and you remember the houses you were in as a kid. I’m seeing the people I grew up with as a kid,” says Simmonds.

“I went into houses in North Preston where I wanted to hide. I wanted to stay back, feeling like OK, they’re going to think, oh, you’re a sellout. By the end of it, I’m talking to them and they’re like, ‘Don’t sit back. Come do whatever you need to do, because I know you’re going to treat me fair.’”

Last month, a bystander video captured the death of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, while in custody of Minneapolis police. The video shows a police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, while Floyd is handcuffed, lying on the ground and repeatedly telling officers he can’t breathe.

Simmonds says he was never taught to kneel on an individual’s neck at any point of his police training

“Even if we do go hands-on with somebody, we’re trained, when they are under control, now we serve them. Now we protect them. We make sure they get home safe or to the hospital safe, or cells, right, safely,” says Simmonds.

“The people I work with, the people I know and I love, I work with in Cole Harbour, North Preston, they come to work every day and put that vest on, they’re there to help. I can trust them, I know when they’re going through the community they don’t see colour. It’s heartbreaking, it hurts. I fear for my family and my kids growing up. It’s 2020 and we’re still dealing with this.”

When he was growing up in North Preston, Simmonds says his father taught him to be respectful when interacting with the police.

“Diffuse everything and if something goes bad, he’ll handle it, not me. I don’t have to react and go home, or wherever it may be that they take me or what happens, but he’ll handle it,” recalls Simmonds.

Simmonds was inspired to be a police officer when his high school law teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he was older.

“When he picked me I said, ‘I don’t know,’ and I just laughed. I remember his face going quiet, because the rest of the class laughed, and then he continued to stare at me. He said, ‘No, no, Justin, what do you want to be?’ I was like, ‘I don’t know,’ says Simmonds.

“In my head I’m like, I don’t know, I’ve never been asked that question, and I feel that most Black kids aren’t asked that question, and when he asked me, my law teacher, he said, ‘I see you being a police officer.’ Boom -- a white man picked me out of this white class and he could have said that to anyone, and he said to me, ‘I see you, Justin, being a police officer,’ and that was it.”

Now, when Simmonds is speaking with children, he makes sure to end the conversation with, “What do you want to be when you get older?”

“It's just an awesome feeling. It’s an awesome feeling just to know, just to know somebody, that has no reason to love you or think you can do well … that doesn’t owe you anything, can say that. It’s just an awesome feeling. So I took that with me throughout my career,” says Simmonds.

When he puts on his RCMP uniform, Simmonds says he is looked at differently.

“When it’s on, I’m a part of the so-called white privilege, I would say. I’m Black, but I’m still a part of the white privilege. Being given this privilege, I need to do something about it, right? I have to stand up for what I believe in, my community and my police officers I work with,” says Simmonds.

“We get up every morning, we put that bulletproof vest on, when that goes on your mind goes to, OK, it’s time for war. It takes a toll on you. You’re going to war, I’ve got a rifle, I’ve got a handgun. You can’t put that vest on every day and not go out there with the intention to help. There’s a chance you won’t come home to your family. I’ve got to come home to my kids.”

Simmonds has two children, a daughter and a son, and says he teaches them about racism.

“It’s hard to have that talk to your children, right, at such a young age. But I think back to what Martin Luther King said back in 1963. He has a dream that one day his children won’t be recognized by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character, so I hope one day that Riley and Crewe will have that,” says Simmonds.

“But we sit here today almost 60 years later and we’re still here.”