By Bill Dicks, CTV News

As opioids continue to exact a deadly toll on Canadians, and officials here in the Maritimes lay the groundwork to deal with this growing crisis, it may come as a surprise to hear, just across the border in the State of Maine, hundreds have died from drug overdoses.

Most of those deaths can be attributed to opioid abuse, which authorities are calling an epidemic.

In Maine’s largest city, Portland, there is the Milestone Foundation. It is a 16 bed, standalone in-patient detox centre.

It is the only one in the state. Milestone is forced to turn away two to three people a day who are looking for help because their beds are full.

Among the clients at Milestone, is a young man named Wayne. He is 27 years old, and has been using since he was a teen.

“I started using pills, pills led to morphine, morphine led to heroin,” he says.

An all too familiar story among the thousands hooked on opioids throughout Maine.

“It’s taken everything, I don’t have nothing anymore,” Wayne says about the drugs. “I’ve had my good spells where I do good, have stuff, and slip up once and everything is gone again.”

Dr. Mary Dowd is Milestone’s medical director. She has worked in addiction services for the past 10 years, and sees clients like Wayne every day.

“I feel like we’re losing a whole generation of people,” Dr. Dowd says. “The death rates have gone up primarily due to addiction in people in their 20s, 30s and early 40s.”

Wayne admits, he almost became one of those who didn’t make it.

“I’ve had one overdose, when I was 19. I was with my girlfriend, she was so scared, I was so scared,” he says.

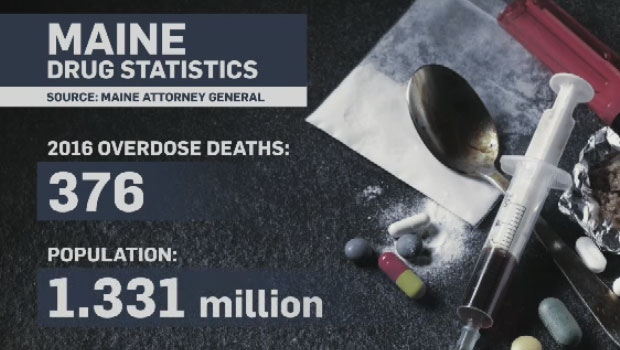

Scared but alive, he is among the lucky ones. Figures from 2016 show 376 people died in Maine from drug overdoses. That is a 38 per cent increase from the previous year, with no sign of these numbers letting up this year.

Maine’s population is just over 1.3 million people.

To compare, Nova Scotia’s population is just shy of 924,000. In 2016 there were 54 opioid related deaths in the province. So far this year, there have been 24 deaths and five probable deaths related to opioids.

Last year in New Brunswick, 51 one people died of drug overdoses, 29 were opioid related. The population in that province is just over 747,000.

With a population of nearly 143,000, there were 10 confirmed opioid related deaths on Prince Edward Island between 2014 and 2016, with the results still pending on four other cases. A couple of deaths involved fentanyl, which is a powerful synthetic opioid painkiller that is similar to morphine but is 50 to 100 times more potent.

Dr. Dowd says Milestone once dealt mostly with alcohol related addictions, now opioids are taking the lead. And it’s this latest manifestation of addiction that troubles her most.

“It’s really taking over our culture and our lives, and I don’t think it’s just because it’s what I do all the time,” she says. “I think it’s everywhere and not much is happening about it.”

Dr. Dowd estimates in Maine there are eight to 10,000 people receiving some form of treatment for drug addictions, but there is an estimated 25,000 using opioids who are not getting any.

In many cases it comes down to money, and no insurance to get into a program.

“There are more laws in Maine restricting the use of opioids for chronic pain, which are a good thing in some ways, but in other ways we’re seeing more and more people who are now losing their chronic opioid prescriptions and they’re needing to detox, and there’s not much alternative,” she says.

Of course, when people can’t fill prescription, many turn to the street where they can find cheap heroin, something readily available in Maine.

Among the communities hit hardest by this crisis, Portland. The chief of police admits his city was caught off guard.

“The opioid issue and epidemic in the country has been on the radar for probably the last four or five years, but certainly in the city of Portland, we noticed in July of 2015, we had a real direct impact with 14 overdoes in a 24-hour period,” says Chief Michael Sauschuck.

There were 46 fatal overdoses in Portland in 2015, another 42 in 2016. Police, including Chief Sauschuck, now carry Narcan, a lifesaving antidote used to bring those who overdose back from the brink.

Since September of last year, Portland police have used Narcan 50 times.

The chief admits the crisis has forced a rethink among law enforcement, officers now know they can’t arrest themselves out of this epidemic.

“You have to look long-term in the prevention world, education and working with youth and working with families,” he says. “Treatment is imperative, and trying to develop and partner with treatment opportunities while we’re continuing to provide enforcement.”

That police work includes keeping an eye on entry points leading into the state. Chief Sauschuck says the I-95, the highway running from the New Brunswick border all the way to Florida is an easy corridor through Maine.

Dealers are buying cheap heroin from Mexico and moving it north by car, bus, train, and even boat. Suppliers from as far away as Atlanta and New York are showing up and turning a profit by buying cheap and selling high in Maine.

“They buy their drugs in their local communities and they may triple or quadruple their money by coming up the Interstate, by coming to Maine to sell,” says the chief.

Making matters worse, he adds, fentanyl and carfentanil from China are ending up in his state. These cheaper synthetic drugs, along with the heroin are making for a deadly cocktail.

Back at Milestone, the centre’s executive director echoes what many in the state are saying.

“The challenge that we have in Maine is that we don't have nearly enough services really on any level throughout the continuum to accommodate the need,” says Bob Fowler.

And that need transcends boundaries, opioid abuse cuts across all levels of society.

Fowler says, by the time he sees them, many have lost nearly everything.

"Over half the people we serve don't have health insurance and so their prospects of receiving services after they leave the detox, is really quite poor,” he adds.

A typical stay in the detox is three to seven days. The average length is around four. All clients are there voluntarily and can elect to leave.

Among the factors contributing to this crisis, Fowler suggests, is the breakdown in families, and people living in isolation.

“People will go into a coffee shop bathroom and leave the door unlocked, so that in the event they'll overdose, somebody will happen upon them. They'll overdose in a porta potty, and leave the door open so somebody will find them. Or, they'll overdose in their cars, with the door unlatched so that if they lose consciousness, they'll fall out and someone will find them,” Fowler says.

For him, seeing this side of Maine and trying to reconcile it with the state he moved to 14 years ago, is difficult.

“Maine is just physically stunning, a spectacular, beautiful state in many ways, and at the same time, we have this, really pernicious, ugly epidemic that's ravaging our state,” he continued. “It's a really unfortunate juxtaposition of beauty and ugliness that lives side-by-side."