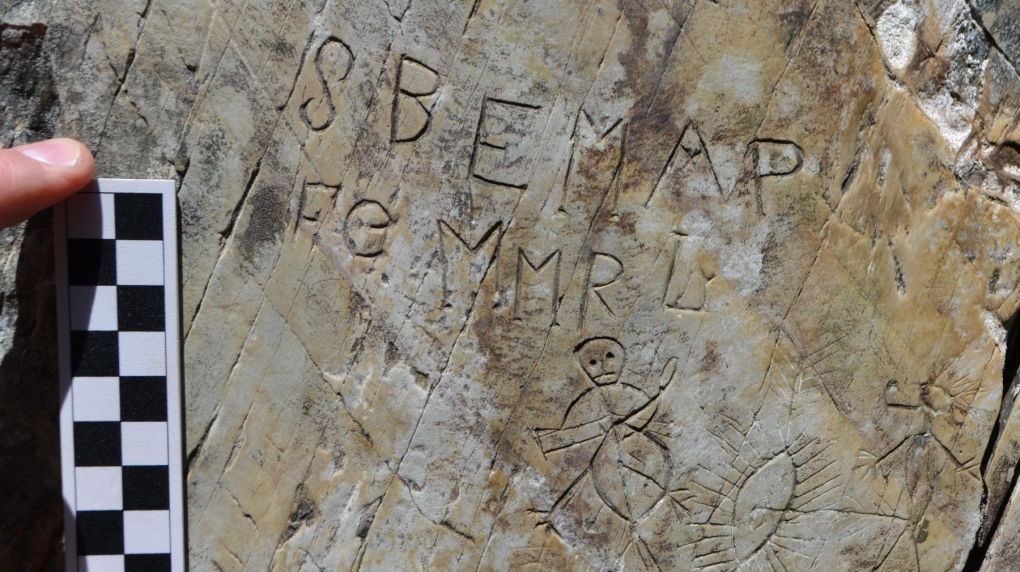

ST. JOHN'S, N.L. -- A small set of petroglyphs the size of an outstretched hand was carved possibly hundreds of years ago into what is today a rocky, lichen-covered crevice in eastern Newfoundland.

Now, archaeologists and the chief of Newfoundland and Labrador's Miawpukek First Nation are seeking provincial protection for the recently unearthed petroglyphs, which appear to be the first Indigenous carvings discovered on the island of Newfoundland, according to those studying them.

The carvings, found by a local resident near Conception Bay North in the fall of 2017, show two human figures and one animal-like figure. The fertility motifs are characteristic of other carvings by Algonquian-speaking peoples that have been found in northeastern North America.

Miawpukek Chief Mi'sel Joe, who visited the site about a month ago, said by phone that the sight of the carvings stirred exciting questions of who may have carved them and why. He said he felt an urge to preserve them.

"It was almost like a spiritual thing, an emotional thing at the same time," Joe recalled of his visit to the site of the petroglyphs. "I didn't want to leave there, almost like I wanted to protect it."

Joe said he was excited when he first saw photos of the carvings, but nothing compared to standing in front of them.

"We've been searching around Newfoundland for the longest time for burial sites (but) never, ever thought to look for petroglyphs," Joe said. "I'm sure they're around."

Barry Gaulton, an archaeologist at Memorial University, agrees. These may be the first Indigenous carvings archaeologists have found on the island, but Gaulton said he hopes the discovery is the start of something bigger, marking a new direction for archaeological research as more local people report such findings.

"I wouldn't be at all surprised that there are many throughout the province," Gaulton said in a recent phone interview from Ferryland, N.L. "Maybe over time we can unravel a much more accurate picture of Indigenous peoples on the island."

The carvings originate from the period after Europeans first arrived in Newfoundland, Gaulton said, judging from the Roman-type lettering above the pictures and the fact that a metal tool like a knife was used to make them.

The weathered carvings have not yet been dated, but Gaulton said they could originate anywhere from the 1600s through the 1800s.

The images, including what looks like a vulva and figures of a man and a pregnant woman, contain similar motifs to those observed in petroglyphs found in Nova Scotia, Ontario and Maine, attributed to Algonquian peoples like the Mi'kmaq, who are among the original inhabitants of Canada's Atlantic provinces.

There are multiple interpretations to the petroglyphs, and archaeologists are still working to unravel the story behind them.

According to a report on the petroglyphs, published by the province's archaeology office in March, the carvings could be read as a life and death scene, "with the copulation motif to the right and a floating corpse-like figure rising above or leaving the body of the anthropomorph to the left."

A second theory suggests the images could represent stages of copulation, pregnancy and birth.

The carvings could also represent a family, Gaulton said of the memorable panel he described as "beautifully carved" and striking to observe face-to-face.

"It's wonderful," Gaulton said. "The first time I saw it, I couldn't stop thinking about it."

The small size of the panel and its location in an isolated, subterranean crevice suggest it was made as a personal, private expression by one individual, Gaulton said.

The exact location of the small piece of history is staying under wraps for now, as possibilities for protecting the site are considered.

Gaulton said meetings with Indigenous leaders and representatives from the provincial government are an important next step towards safeguarding -- and showcasing -- the carvings.

The hope is that preserving the petroglyphs can contribute to a more complete record of Indigenous peoples' history in Newfoundland.

"These things are typically not written about in any kind of detail, so I think the petroglyphs are an extra source of information that we have to paint a much more holistic picture of the movements of people in the past," Gaulton said.