The chief of Nova Scotia’s largest emergency department says the record number of code census calls is a symptom of a much larger problem facing Canadian health care: how to manage the growing number of elderly patients.

The Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union released a report Monday tracking a rise in so-called code census incidents at the Halifax Infirmary, when the emergency department declares the ward is "unsafe" and starts sending patients to in-patient units.

The Halifax Infirmary handles about 250 patients a day and wait times are often long, especially for more minor illnesses.

Many of the elderly patients need placements in some form of long-term care. According to the Department of Health, the wait list for a nursing home placement ranges from 41 days to more than three years, depending on where the patient lives.

Residential care waits range from 15 days to almost two-and-a-half years.

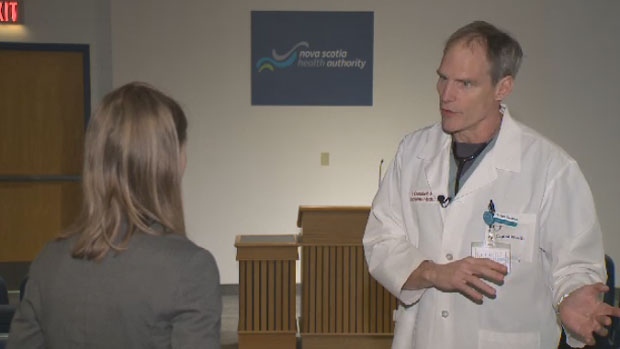

“We’ve got a lot of work to do, we clearly have a crisis,” says Dr. Sam Campbell, chief of Halifax Infirmary’s emergency department. “They arrive in the emergency department because they're not able to cope at home. There's nothing actually wrong with them. There's nothing we can do to make them younger again.”

Brian Butt, in charge of patient flow for the Nova Scotia Health Authority, says long-term care isn't always available where patients live and that home care is used when possible.

“Throughout the province we have available long-term care beds, but there is a bit of a mismatch,” says Butt.

Currently, there are around 45 patients at the QEII Health Sciences Centre waiting for a long-term care placement; Butt says that's less than half of what it was just a few years ago.

As long as patients waiting for long-term care are in acute care beds, there's nowhere to move admitted patients from the emergency department, which leads to code census calls.

“The longer you spend in an emergency bed, when you should be in an inpatient bed, means you are less likely to have a good outcome,” says Dr. Campbell.

Dr. Campbell also says about 14per cent of his emergency patients don't have a family doctor. Those working on the frontlines say the issues are connected.

“People have gone without primary care for up to three years,” says family physician Dr. Ajantha Jayabarathan. “What ends up happening is over that period of time chronic illnesses that otherwise should be managed are not managed.”

Dr. Jayabarathan says she'd like to see immediate investments in long-term and primary care.

With files from CTV Atlantic’s Sarah Ritchie