HALIFAX -- Geoffrey Grantham sits painting the granite slope and wind-blown jack pine reflected in the waters of a Nova Scotia lake, his mind far from the busy city just a short walk away.

It only took minutes for the 48-year-old artist to hike from a big-box retail hub in Halifax's west end into the tranquility of the Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes urban wilderness.

He is among the growing number of eco-tourists -- ranging from painters and bird watchers to walkers and canoeists -- who journey to this area, often by bus, bike or on foot.

"I experience a oneness with nature here ... and I leave the world of daily cares behind me," he said, in between dabbing oils on his canvas depicting Susies Lake in late October.

Many of the visitors here also advocate for the conservation of these lands, with a plan underway by the Halifax Regional Municipality to complete a 2,000-hectare regional park that could rival locations such as Ottawa's National Capital Commission.

"It ties into so many things that are on the public radar these days, from the global biodiversity crisis to advancing Canada's commitment to protect 17 per cent of Canadian lands and inland waters by 2020," writes Bonnie Sutherland, executive director of the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, in an email.

It's estimated the Blue Mountain area contains 1.6 million trees and stores over 200,000 tons of carbon.

Dr. Dusan Soudek, a retired family physician from Halifax, started coming to the area when a friend invited him for an evening swim at Quarry Lake, at the wilderness area's southeastern end, and was startled to realize it was about 15 minutes drive from his home.

He now often takes multiple-day canoe excursions, which involve portaging through the networks of lakes that form a western border to the city.

In winter, he skis and snowshoes.

"It's wild, rugged clean water, and I've been gradually exploring it more and more," the 66-year-old outdoorsman says as he guides a reporter and photographer to a look-off.

He said for decades people have been caring for the informal trail networks, while the effort to preserve the area from developers ramped up in the 1990s, and is ongoing.

The first key steps to consolidating an urban wildland came with the province's designation of two large Crown land blocks as wilderness areas in 2009 and 2015. In 2018 and 2019, the municipality purchased and added 210 hectares of private lands as part of its plan to create a regional park.

The Nova Scotia Nature Trust recently announced a $2.1-million fundraising drive to buy a 230-hectare portion of land a few kilometres further west, after two landowners agreed to sell the vital piece of connecting land.

However, portions of the park proposed by the municipality remain in private hands, particularly at the southeastern end where Soudek launches his canoe.

Richard Vinson, a spokesman for the Friends of Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes, said "as long as that land is privately held and not owned by any public entity there's a risk (of development)."

The group is still meeting with councillors, cabinet ministers and government officials to remind them of their hope to complete the park, he said.

A spokesman for the City of Halifax says the municipality is investigating purchasing properties, and hopes to partner with higher levels of government to help it pay the costs involved to obtain the land from developers.

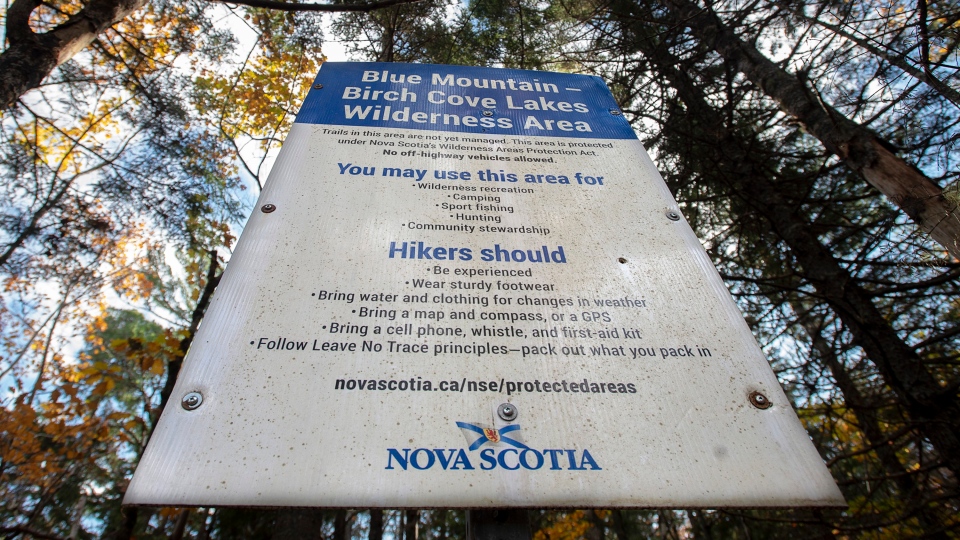

Meanwhile, as efforts to put all of the pieces of the wilderness area together continue, the existing trail only has occasional markers and is not easily accessible to those unfamiliar with the area.

Soudek suggests visitors unfamiliar with the area can seek information on guided walks and journeys with experienced regulars through the Friends of Blue Mountain - Birch Cove Lakes Facebook and website, and the Halifax North West Trails Association. Links to maps are available on the websites as well.

The Friends group website notes, "the trails are not managed or fully signed and as such, can present challenging conditions for the novice hiker."

If travelling alone, Soudek recommends good hiking boots, a cellphone with a backup charger, a GPS, compass and maps that are available online.

"It's a park in the making, not a finished product," he explains.

Still, visitors who ask for help on the group's social media can find help from enthusiasts who promote the concept of an urban wilderness. Currently, the Friends of Blue Mountain Birch Cove Lakes group is planning a course to train 10 hiking leaders.

There's plenty of things to watch for, with over 150 species of birds including loons, osprey and woodpeckers in the area, and many sensitive and at-risk species like Canada warbler, olive-sided flycatcher and common nighthawk present in the area.

Meanwhile, for Grantham, the natural world he's turning into a canvas is a journey he'll continue to make regularly.

"I'm glad to hear this is moving forward and becoming protected," he said.

IF YOU GO:

- The simplest entrance to the planned park is just behind the Kent hardware store in the Bayer's Lake Business Park. There are also entrances at Collins Road, via Belle Street and Kearney Lake Road, and at Anahid Drive, in the Kingswood subdivision.

- If you're new to the area consult the website of the Friends of Blue Mountain - Birch Cove Lakes at www.bluemountainfriends.ca for details, under the "Activities" section, where basic hiking routes are posted. The group also has a Facebook page.

- Participants are encouraged to join the non-profit group in order to participate in "members only" hikes and activities.

- When travelling in a wilderness area, travellers are encouraged to plan route carefully, leave a written plan with someone outlining your route, and to carry and be knowledgeable of how to use first aid and safety equipment.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 4, 2019.