HALIFAX -- The leaders of Nova Scotia's main opposition parties say they're getting an earful from voters about education on the provincial campaign trail.

"It's big," NDP Leader Gary Burrill said as he campaigned for the May 30 vote.

"It's not at all uncommon that a person comes to the door ... and they say, 'I'm glad you're here. I'm a teacher and we can't wait to do something about the present government.' That happens a lot."

The twin strands of the issue -- concerns over conditions in the classroom, and over the Liberal government's hard-line approach with the teachers' union -- have amounted to a perfect political storm for Premier Stephen McNeil.

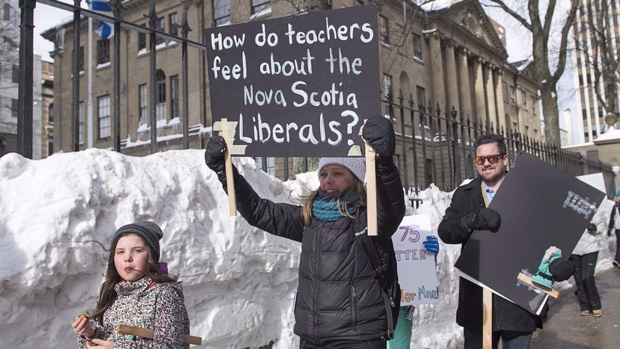

In mid-February, tensions boiled over as thousands of angry teachers, having rejected three tentative contract deals, staged noisy protests outside the provincial legislature. Inside, scores of others told a legislative committee that violence in the classroom and neglect of special needs students would worsen if the government imposed a collective agreement.

And that's exactly what the Liberal government did after a one-day teachers strike, the first in the province's history.

"I've had more members of the public talk to me about the testimony that they watched at the committee than almost any other issue," Progressive Conservative Leader Jamie Baillie said in an interview.

Liette Doucet, president of the Nova Scotia Teachers Union, said it's clear voters are not happy with the way the government has treated the province's 9,000 public school educators.

However, Doucet said she was pleased the Liberals agreed before the election to set up two committees to provide recommendations on improving classroom conditions and revising the province's inclusion policy for special needs students.

"We've been asking for this for years and years," she said. "All of a sudden, those things are happening."

Late last month, the council reviewing classroom conditions recommended the province hire 139 more teachers this September, and it also called for caps on classroom sizes at all junior and senior high schools.

McNeil was quick to accept the council's 40 recommendations. Two days later, he announced that Nova Scotia voters would be going to the polls.

At the time, council member Michael Cosgrove, a teacher at Dartmouth High School, said hiring more teachers was important because it will help reduce stress in "some of the complex classrooms."

Cosgrove's comment echoed the chorus of complaints teachers had shared at the legislature as the government was preparing to impose a four-year collective agreement with a two-year wage freeze.

One after the other, teachers complained about crammed classrooms and their inability to cope with a rise in student mental illnesses.

Many said there just wasn't enough support to help the most vulnerable students.

One teacher talked about having 30 students with vastly differing abilities jammed into an obsolete laboratory designed to hold about 20 students.

Meanwhile, the committee looking into the province's inclusion policy for students with special needs is expected to submit a report next month -- after the election.

That issue has touched a raw nerve with many teachers, some loudly complaining they need help to deal with students with a wide range of mental, physical, behavioural and learning challenges.

While no teachers appear to be calling for a return to segregating students with special needs, some have come forward to suggest inclusion isn't working because teachers don't have the resources they need.

Others have suggested caps on the number of students with learning disabilities, but Education Minister Karen Casey has dismissed that idea.

Meanwhile, the Education Department has said about 20 per cent of Nova Scotia's 118,000 students need some form of curriculum support, while about five per cent require a so-called individual program plan, a proportion that is in line with other Canadian jurisdictions.

As well, Autism Nova Scotia has said the number of kids diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder has increased by 30 per cent since 2008.

The teachers union is calling for more psychologists, guidance counsellors and resource teachers.

"Class composition is really ... more important than class size," Doucet said. "We really do need to see significant changes when it comes to inclusion."

McNeil said his government had to settle a collective agreement with the teachers before it could deal with the many issues raised during the 16-month labour dispute, which was easily the nastiest confrontation the premier has faced since the Liberals assumed power in 2013.

"The (union) wouldn't let their teachers speak to us (until a contract was reached)," he said. "We would have been accused of unfair bargaining if we went to teachers."

Despite the fact that the government has made strides in dealing with teachers' concerns, it's clear that the labour dispute hurt its popularity.

"Without question, the (labour) unrest that went on impacted the satisfaction levels," said Margaret Brigley, president of Halifax-based Corporate Research Associates. "In previous quarters, there was very little movement, and then suddenly a decline."

In mid-March, the research firm released the results of a month-long survey of 1,200 people that suggested decided voter support for the Liberals had declined sharply since the previous quarter to 44 per cent from 56 per cent. Polls since suggest the race has only tightened.

Jeff MacLeod, a political studies professor at Mount Saint Vincent University, said McNeil's tough approach may have tarnished his image.

"When he seems under stress or being challenged, he can appear rattled and even annoyed," he said. "That's where his government is most vulnerable: his personal image."

Through it all, McNeil has maintained his government's commitment to balance the province's books would have been derailed unless the growth of public sector wages was reined in.

"We didn't take anything away," he said in an interview while campaigning in Halifax. "We had to slow the growth down. A lot of teachers were OK with that."