OTTAWA -- The Trudeau government has embarked on its long-awaited review on the future of the Canadian Armed Forces, something it hopes to have completed in time for the next federal budget cycle.

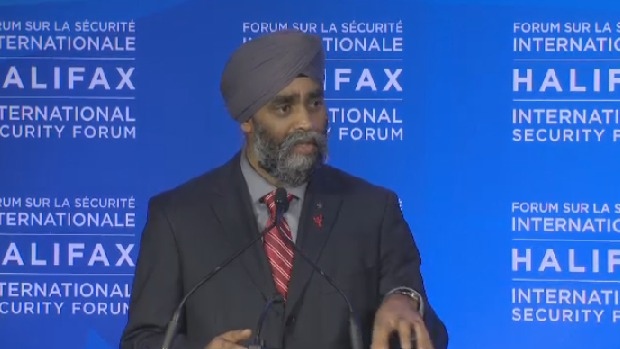

Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan laid out the process Wednesday and asked for public input.

"We need to do a defence review to actually determine not only the capabilities that we need, but also help us with how they're going to be employed," Sajjan told a news conference.

"The defence review is going to be the guiding principle for this.... It's not just about having the necessary tools. How you employ them is also critical as well."

Consultations will take place between now and the end of July and will look at the future size of the military, the kinds of missions it will undertake and the type of equipment it will have.

The Liberals already have a clear idea of where they believe the military fits within Canada's foreign policy framework, having promised during last fall's election campaign to end its bombing campaign against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in favour of a new training-focused mission, as well as renewing the country's traditional focus on United Nations peacekeeping endeavours.

That said, Canada has had a checkered history when it comes to laying out and following through on its defence priorities.

Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, the commander of the Royal Canadian Navy, told a conference last week that the last defence strategy -- cobbled together under the Harper Conservatives in 2008 -- was more of an "in-house product" that reflected desires and opinions coming from within the government.

The so-called Canada First defence strategy laid out an ambitious wish list of equipment to be purchased, most of which ended up becoming either unaffordable within a year of the plan being announced or stuck in a moribund procurement system.

Prior to that, the last attempt to fashion a defence strategy came in 1994, when the Chretien government wrote a full-fledged white paper, most of it aimed at slashing spending and reducing the ranks.

It mandated a cut in the number of full-time members to 60,000, a reduction in reservists to 23,000 and the wholesale streamlining of National Defence headquarters.

Two decades later, Justin Trudeau's Liberals promised a "leaner, more agile" military and to follow through on reductions at DND.

The 1994 white paper also promised to replace the air force's Sea King helicopters and the navy's aging supply ships -- purchases that still haven't been completed.

Before that, the Mulroney government in 1987 produced a white paper that called for, among other things, acquiring nuclear submarines to patrol under Arctic ice. The end of the Cold War two years later and massive defence cuts that were part of the so-called "peace dividend" left many of those plans in tatters.

Therein lies the lesson, say defence analysts.

Retired colonel George Petrolekas of the Conference of Defence Associations Institute said the Trudeau government has not defined what it considers to be affordable.

Until it does, the public and the defence community will be spinning their wheels on a whole series of good ideas that could potentially go nowhere, he warned.

"I just think we're throwing darts against the wall to see what sticks," Petrolekas said. "If it is not wrapped within a fiscal framework and fiscal wherewithal, it means nothing."