FREDERICTON -- There is a growing movement on New Brunswick's First Nations to banish drug dealers, as mourners said farewell this week to a woman who died of a drug overdose.

Leo Bartibogue, an addictions counsellor, says there are 30 to 40 drug dealers in his community of Esgenoopetitj, in northeastern New Brunswick, and it's hard for people to quit when there's an ample supply of drugs at every turn.

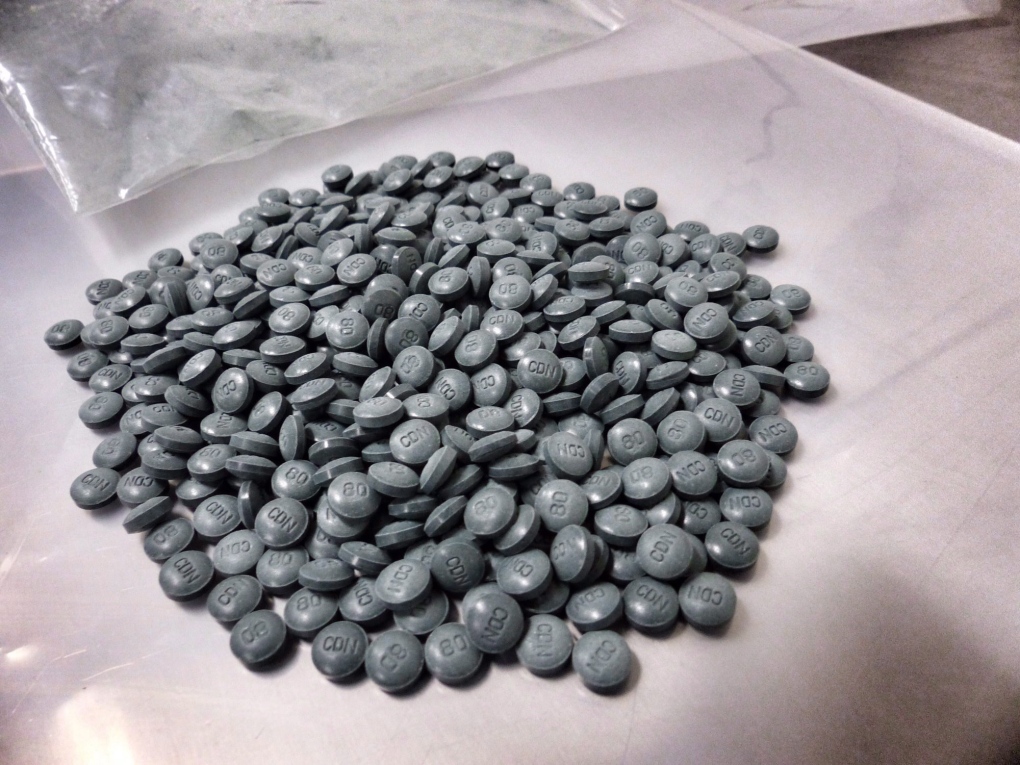

Bartibogue attended the 35-year-old woman's funeral on Monday and says it's suspected she may have taken fentanyl -- a powerful synthetic opioid drug that has killed hundreds in western Canada but is relatively new to the East Coast.

"We have so many routes that come in through our community that people seem to prey on, bringing these drugs all the time into our community, so we don't know what we're getting," Bartibogue said.

RCMP Cpl. Maxime Babineau said while an autopsy has confirmed an overdose, police have yet to confirm the drug, and are awaiting test results from Health Canada, possibly later this week.

"We have placed an urgent request for the results," Babineau said Tuesday.

Bartibogue said the band council has suggested a resolution to ban drug trafficking, as the Elsipogtog and Tobique First Nations have done, and he's in full support.

Tobique Chief Ross Perley said, under a banishment resolution passed last week in his community, anyone charged with drug trafficking would be cut off from all band services and benefits.

"Our hope is that they'll reconsider what they're doing to their people if they risk losing potential employment, housing benefits, royalties or things of that nature," Perley said.

Both Perley and Bartibogue say children as young as 10 years old are buying drugs.

Perley said he knows of about a half-dozen drug dealers in his community and most are dealing in opioids and prescription drugs, rather than more expensive drugs like cocaine.

"They're cheap. You can get them anywhere. The traffickers are getting them legally by the local pharmacists, so the access to these types of drugs are really easy," he said.

"This is the start of us, as a community, a united community and a united leadership taking a stance on drugs in the community."

According to the New Brunswick coroner's office, there were 43 drug overdose deaths in the province last year. That's down from 51 in 2015 and 70 in 2014.

Those statistics account for both legal and illicit drug toxicity deaths.

Esgenoopetitj Chief Alvery Paul has warned his community on social media.

"With this recent death and near fatal overdoses, we as parents, family and community must work together to stop the selling of drugs entering our community. I understand this is a battle that we can't win overnite but we have to educate our young children," he wrote on his Facebook page.

RCMP Sgt. Chantal Farrah said police are doing what they can to stop drug trafficking, but they need public help to identify the sellers, which can be done anonymously through Crime Stoppers.

"Taking any type of illegal drug, you never know what's really in that drug because it's done on the black market, so you are taking a gamble with your life. It's like Russian roulette and you're putting something toxic in your body that could kill you," she said.

Several Saskatchewan First Nations have made similar moves.

The Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation last year banished six non-band members and gave warnings to more than a dozen members because of a crystal meth problem.

Muskoday First Nation, Mistawasis First Nation and the Lac La Ronge Indian Band have also banished people to help control crime. And the chief of Saskatchewan's Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations said he supports bands that want to exile criminals.