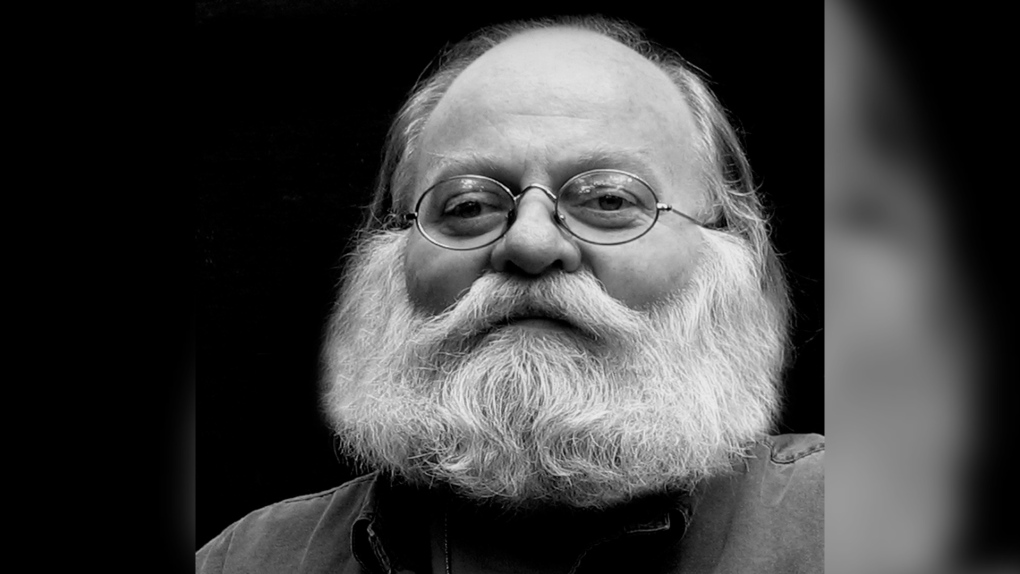

HALIFAX -- When poet Sue Sinclair heard of Don Domanski's death earlier this month, she sat outside her home and contemplated her late colleague's views on life.

Domanski, a Governor General's Award winner who died of a heart attack Sept. 7 at the age of 70, was interested in the interconnectedness of the universe and insisted that the beings in it were part of a certain "oneness," she said.

"It kind of helped to think of his death as being part of a larger rhythm of life into death, into life into death, into life into death," Sinclair said in a recent interview.

Her relationship with the Nova Scotian poet was new. She helped edit his most recent collection of poems, "Fetishes of the Floating World," which is set to be released in fall 2021.

In it, Domanski, muses about the liminal space between waking and sleeping, and about crossing between the two realities. The poet fuses together mystical and scientific language in the manuscript, a feature Sinclair said is found in his previous work.

"(He was) kind of a genius of perceiving relationships in the world that not just everyone sees and communicating them in such a way that you kind of 'get it' in a flash in his poetry," she said.

That sentiment was echoed by some of his peers in Canadian poetry.

"He could vault you into another world with a single comparison of two things," Tim Lilburn, a poet and writing professor at University of Victoria, said in a recent interview.

Lilburn, a longtime friend of Domanski, said they shared a mutual admiration of each other's work. "No one else wrote like him. No one else had the strength of imagination."

Like Sinclair, Lilburn said he marvelled at the distinctive nature of Domanski's metaphors. He said he was also impressed by the poet's lyrical rhythm and his exploration of theology, botany and mythology.

Canadian poet Brian Bartlett said Domanski's approach to myth and to history made the late writer a unique force in the country's poetry scene.

Domanski often spoke in "ancient voices," imbuing his work with a "timeless quality," Bartlett said in a recent interview. Domanski, Bartlett added, was aware of man's small place in the universe.

"He had a deep sense of time, of not just human time, but of geological, sort of cosmic time."

Domanski's poetry was often concerned with the nature around him, Barry Dempster, another close friend and contemporary of Domanski, said in a recent interview. "He had a way of approaching nature in all its carnage and beauty and fear and joy and making it something that was just quite remarkable."

Dempster said Domanski was able to skillfully transport a reader into a dark space without it being overwhelming.

"His poems had a buoyancy to them," Dempster said, "but he also could go deep into the darkness in the poems without making you feel like you are being pressed into a hole into the ground."

Lilburn said Domanski "opened a whole new wing" of Canadian poetry. "The wing of the imagination. Not imagination as fancy, but imagination as a form of thinking, as a form of being in the world."

It was that connection to the world that inspired his readers, Domanski's wife, Mary Meidell, said in a recent interview. He described himself as a "metaphysical poet," she said, adding that his spiritually was reflected in his work.

"I think a lot of people felt it gave them a sense of the sacred," Meidell said. "He saw poetry as a sacred endeavour and other people were able to connect with that."

Domanski's effect on Canadian poetry goes beyond his style, she said.

"He saw himself in a time where art in general -- and poetry, for sure -- is in a dangerous situation and he felt that, as a poet, it was his role to create a safe and enduring place for poetry. And I think he achieved that," she said.

"Don was his work. Don was poetry."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 24, 2020.