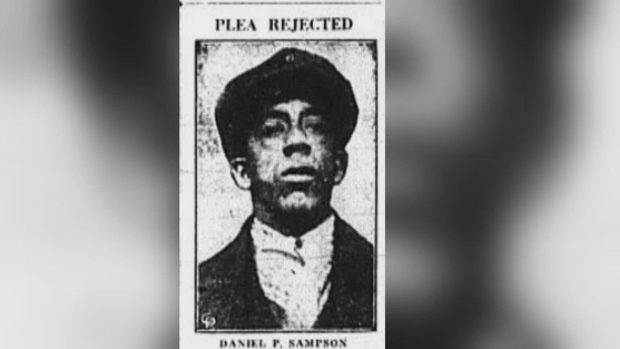

On Thursday, March 7, 1935, an unemployed labourer named Daniel Perry Sampson walked up the stairs on the gallows constructed behind a Halifax courthouse, making him the last person ever to be hanged in the city.

But nearly 85 years later, some are convinced he got a raw deal from the justice system.

Sampson, a black man, was arrested and charged with two counts of murder five months after the bodies of two white boys, brothers 10-year-old Edwin and 12-year-old Bramwell Heffernan, were found along the train tracks in Halifax’s Chain Lake area.

‘Inseparable pals’

Edwin and Bramwell came from a good family and were raised by Salvation Army officers. The Heffernans would have been considered the epitome of upstanding citizens at the time. The brothers would later be described as "inseparable pals" by newspapers. The last known photograph of the boys shows them celebrating a birthday with their baby sister just a few days before their bodies were found.

When the boys failed to come home for supper after going berry picking, their father, Edward Heffernan, went looking for them with a friend. The two men found the body of the first boy laying along the railroad tracks.

“He picked him up and carried him halfway home, but had to lay him down,” says Debra Taylor, a niece of the Heffernan brothers. “He was, I guess, so distraught over that. His friend carried him home and they laid him on the kitchen table.”

The second boy was found a short time later. Given the location of the bodies, authorities assumed they'd been hit by a passing train. An inquest was convened, but the results were inconclusive. The coroner noted what appeared to be stab wounds in the bodies, and the inquest resumed, urging police to keep digging.

Debra's mother, Edna, who was 96 when she died in 2016, never forgot her younger brothers, faithfully noting their birthdays on a calendar every year. While Edward Heffernan eventually learned to cope with his grief, his wife died of a broken heart.

"My grandmother was never apparently the same,” she says. “It destroyed her, losing those boys."

Searching for justice

Daniel Sampson's legal odyssey would drag on through two trials and appeals all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. But the conviction stood and Sampson was sentenced to hang.

Even an appeal for mercy by the boy's father fell on deaf ears.

“(Edward) asked the court, I guess, for this man, Mr. Sampson, not to be hung. And that just went by the wayside," says Debra.

The execution was over in minutes, including the paperwork. The medical examiner listed Sampson’s cause of death as hanging, but his death certificate was more specific; it stated Sampson had been “executed by order of the court.”

Sampson’s mother had been a constant presence through the legal process, and newspapers reported that she had visited her son the afternoon before he was hanged. What they failed to report was that Sampson had a wife and a son.

The Sampson family has never spoken publicly about the case until now. His widow, Rita-Mae Sampson, lived in the same Halifax neighbourhood until her death in 1984. Their son, Arthur, was 48 when he died in 1970. He grew up to become a cook in the Canadian navy, but was bullied relentlessly as a child.

"They used to tease him about being a murderer's son,” says Carolyn Sampson, Arthur’s daughter.

As time passed, the Sampson family began to question what really happened all those years ago, and have started to view Daniel Sampson in a new light.

"He had a family. He was a person. He had a wife. He had a child. You know, nobody knew this,” says Paula Crawley, Daniel Sampson’s great-granddaughter. “He was just Daniel P. Sampson, a man hung for murder.”

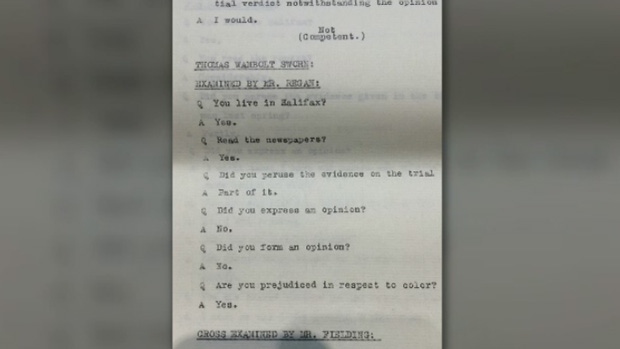

Questions continue to linger about the kind of treatment Daniel Sampson received from the Nova Scotia justice system. For starters, he would hardly be judged by his peers; every juror in both trials was white. At the time, jurors in Halifax were chosen from 10 specific polling areas, meaning black people were geographically shut out.

“None of them were in the north end of Halifax,” says lawyer and legal historian David Steeves. “None of them were in areas where African Nova Scotians would live, and effectively that excluded African Nova Scotians from sitting on juries until about the 1940s.”

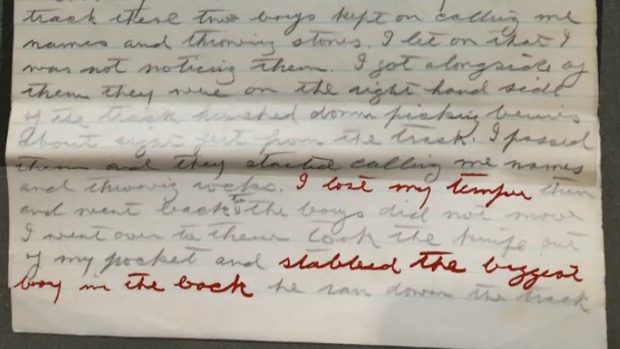

Just hours before he was led to the gallows, Sampson had signed a handwritten confession. It was transcribed by a third party, and is still on file at the Nova Scotia Archives. Unable to read or write, Sampson’s only direct contribution was a small "x" beside his name. In the document, Sampson said he was being harassed by the boys as he picked berries. They called him vulgar names and threw rocks at him.

"I lost my temper," the letter reads. "Stabbed the biggest boy in the back… stabbed the other boy … and threw the knife in the woods."

It's a story that's always sounded fishy to the Sampsons.

“He was on death row for what, a year? He was in prison for a year. He appealed the conviction in the first place, and then all of a sudden, one day his mom goes to visit him and he confesses?" asks Paula Crawley.

Emotions ran high through the legal proceedings. Sampson's lawyer, Ormand Regan, produced a letter saying his client was being threatening by a lynch mob. Regan did his best to create reasonable doubt by cross-examining witnesses who said they'd been asked to identify Sampson in a police lineup in which he was the only black man.

Documents on file at the Nova Scotia Archives reveal Regan also asked potential jurors directly if they were prejudiced against “coloured” people. Some answered, “yes.”

Regan would also argue that Daniel Sampson was likely insane, but the Crown produced doctors who disputed that. They did, however, concede he had a low IQ and could be mentally challenged.

The Sampson family says the truth was much different, noting Daniel Sampson was a First World War veteran serving with the celebrated Number Two Construction Battalion.

"Not mentally challenged, but he was shell-shocked from the war,” says Carolyn Sampson. “Grandmother said he would tie food up in the beams of the house and stuff, just like he was still in the war."

Military records show Sampson served in France, but was reprimanded a number of times for refusing to obey orders. Discharged in 1919, he was sent on his way with just $70 to his name.

Curiously, years after his death, someone updated the military file to reflect the execution.

"I think it was a big miscarriage of justice,” says Paula Crawley. “I think that somebody had to be blamed. I think that Daniel P., the mentally ill black man who wandered a lot, was the perfect person to blame."

Tale of two families

Nearly 85 years after the hanging, in an iconic tea room in Halifax’s west end, ancestors of the Heffernans and Daniel Sampson came together for the first time.

While both admitted the get together was somewhat uncomfortable at first, they chatted for more than an hour about their shared history, and exchanged contact information.

They plan to visit the Nova Scotia Archives together in the new year to research the case together.

"I feel like we have something in common,” says Paula Crawley. “I feel that, you know, finally after all these years, that it's a good thing."

“It’s sad”, says Taylor, her voice breaking. “It’s sad for my mother, sad for her sisters, sad for the Sampson family.

"It’s a sad thing.”

With files from CTV Atlantic’s Bruce Frisko.