HALIFAX -- Gerry Morrison's childhood memories of life in the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children are painful, but he has agreed to re-live them so a ground-breaking virtual-reality project can ensure future generations will never forget.

The 64-year-old is one of three narrators who will take students wearing Oculus Rift headsets on simulated walks through the now-vacant orphanage on the eastern outskirts of Halifax, once the pilot project is prepared for four Grade 11 classrooms by the fall of 2018.

Sent to the residence as an infant in the early 1950s, Morrison said his earliest recollection of the residence was of being in a bathtub with four other children when another resident defecated in the basin.

The matron blamed him, and ignored his denials, he said.

"She had a predetermined hate ... she said, 'You did it,' and I said 'No, I didn't.' She jabbed (the fecal matter) into my mouth until I actually swallowed it," he recalled.

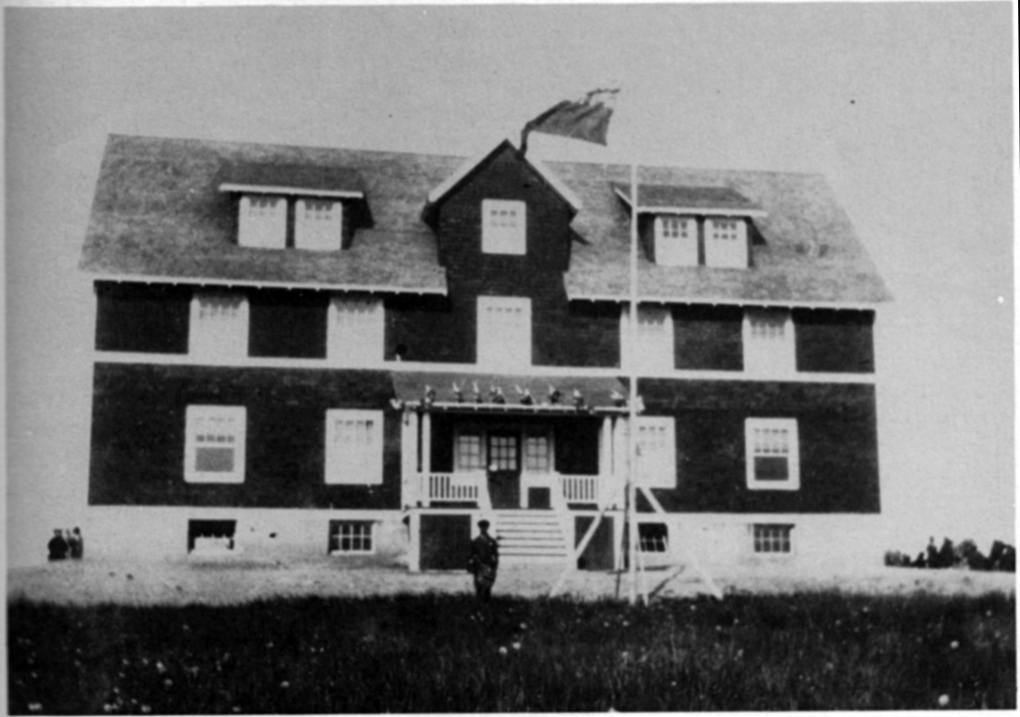

It was part of a childhood spent feeling alone and frightened in the home, which was the site of alleged mistreatment and abuse from the 1940s through until the early 1980s. The home was opened in 1921.

The home was the subject of an RCMP investigation that was eventually dropped in 2012 after police said they had difficulties corroborating the allegations of sexual and physical abuse. However, class-action lawsuits launched by the former residents against the home and the provincial government ended in settlements totalling $34 million, followed by a public apology from the premier.

Morrison said Nova Scotians need to hear his voice and imagine how children struggled with isolation and a sense of neglect in the underfunded home where hundreds of black children spent their childhood.

"Younger kids in the school system don't realize this kind of racism and discrimination happened," he said during an interview.

Facing past errors is how the future changes, says Kristina Llewellyn, a University of Waterloo professor who specializes in oral history and is leading the development of the project, titled Digital Oral Histories for Reconciliation.

She says so-called "serious gaming" is increasing in high school education, but its use as an oral history of how racial groups were mistreated is pioneering.

"This is truly a ground-breaking case study for reconciliation education," said Llewellyn in a telephone interview.

The three-year project will be used in African Canadian Studies and Canadian History classes, with students expected to start donning Oculus Rift goggles and combining the virtual reality with written materials and other resources.

Fifty-two-year-old Tracey Dorrington-Skinner, who was in the home in the 1970s, says she hopes her narrations show the hardships and help illustrate how she survived.

She recalls a warren of basement hallways that were considered dangerous areas, and wants to tell of how she was sexually, physically and psychologically abused beneath stairs by other residents.

"If you see the amount of space under the stairwell you'll be able to see why things happened there," she said.

"It's a way to share our stories in a way that people get it. It's not just people reading you something from a history book. It's somebody actually walking you through it."

Alec Couros, a University of Regina education professor, said virtual reality can -- like first-person encounters -- help students develop empathy for another person's story.

However, he says that the development team will need to bear in mind that powerful content may be disorienting to some students, and consider providing advance warnings of the content.

"As it gets more and more real, what stresses are we putting on students? At what point is it a strategy for empathy versus a tool for distress? It's something where we have to find the balance," he said in a telephone interview.

Sean Kharaj, who teaches a course in digital history at York University in Toronto, said it's critical -- given the power of virtual reality -- that the reconstructions be very accurate.

"The potential for the creation of a false perception of presence in the past is there ... you run the risk of creating a powerful illusion of time travel," said the historian.

The third narrator in the project, 56-year-old Tony Smith, works for a support and advocacy group for former residents.

He says teaching the high school students about wider problems that led to mistreatment, including per-child public funding that was a fraction of other facilities, will be part of the project.

Smith, Dorrington-Skinner and Morrison are also among residents advising a restorative inquiry that's been funded by the province.

The inquiry is providing former residents a forum to discuss their experiences and prepare recommendations aimed at improving the lives of black Nova Scotians and other children who are cared for by the province or in foster homes.

A preliminary report from the restorative inquiry into abuse at the home has said some black people attending its information sessions are still reluctant to interact with public agencies because they feel they are treated as "second-class citizens."