TORONTO -- A court ruling that threw out a New Brunswick man's $292.50 fine for buying cheaper beer in another province and taking it home has upended decades of legal thinking and strikes at the heart of Canadian federalism, the provincial government argues in a request to have the country's highest court weigh in on the case.

The ruling and a refusal by the province's Appeal Court to review the decision, the request states, could hamper government control over interprovincial trade and create nationwide confusion around the extent of provincial authority.

"The combined effect of these two decisions calls into question several judgments of this court beginning in 1921 as well as 150 years of constitutional compromise," the New Brunswick government says in its memorandum of argument to the Supreme Court of Canada. "This is a decision of polarizing national interest."

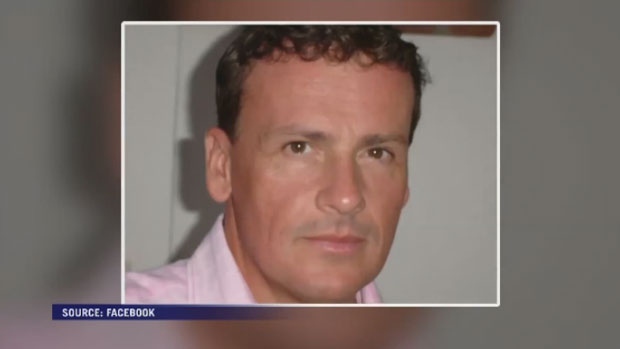

In October 2012, RCMP fined Gerard Comeau, of Tracadie-Sheila, N.B., for violating a New Brunswick liquor law as he returned from a regular beer run into Quebec with 14 cases of beer and three bottles of liquor. The law -- related to federal anti-smuggling efforts implemented at the height of Prohibition -- barred importing more than one bottle of wine or 12 pints of beer -- about 19 regular bottles -- from any other province.

Comeau, a retiree, argued at trial that the law violated part of the Constitution he said mandates free trade within Canada. Judge Ronald LeBlanc last April agreed. The province appealed but the New Brunswick Court of Appeal refused to hear the case.

Even though LeBlanc's decision is not binding, the province is now urging the Supreme Court to decide the case in light of what it says is the national importance of the issues at hand.

"The judgment of the provincial court lays the base for a national contest between interprovincial free trade and the regulatory authority of the provinces and the federal government," the filing argues.

It also notes that Comeau, backed by the Canadian Constitution Foundation, did not oppose the province's initial attempt to appeal.

Despite having won, Comeau is also urging the Supreme Court to hear the case -- for reasons different from the province.

In his reply, his lawyers argue federal and provincial governments have repeatedly violated Section 121 of the Constitution since the country's founding in 1867 by erecting protectionist barriers -- such as New Brunswick did with its alcohol import restrictions, although beer is just one part of a much bigger picture.

A Supreme Court ruling from 1921 that interpreted the provision far more narrowly than LeBlanc allowed governments to erect a "plethora" of interprovincial trade-barriers around alcohol, wheat and even products regulated by provincial marketing boards, the document states.

"These legislative and policy initiatives were created to benefit special interest groups, and now all fall under the shadow of the Comeau interpretation," the document states. "(The interpretation) creates profound economic-rights implications for individuals and for government programs and policies."

As such, the foundation says, it's important for the Supreme Court to weigh in to minimize future legal fights over specific interprovincial trade barriers -- others fights are already brewing -- and to alert governments that they need to adjust programs and tax policies.

An analysis last year by Malcolm Lavoie of the University of Alberta's law faculty hinted at just how far-reaching LeBlanc's decision could be.

"The approach...adopted by the trial judge threatens to shift the structure of Canadian federalism, as well as the structure of economic regulation in Canada," Lavoie wrote. "There is simply no question that a robust interpretation of the Constitution's free-trade provision would restrict the power of democratic majorities, especially at the provincial level, to set economic policies."

Howard Anglin, the constitution foundation's executive director, said in a statement that real free trade among provinces would be a massive economic boon to the country. At the very least, the foundation says, a favourable ruling would throw open Canada's closed provincial alcohol monopolies and could spell the end of provincial agricultural cartels.