HALIFAX -- Rose Poirier stood on a hill overlooking Halifax harbour at 9:04 a.m. Wednesday, quietly marking the moment precisely 100 years before when the city's bustling north end was obliterated by the worst human-caused disaster in Canadian history.

Before the poets and the politicians spoke at a ceremony marking the grim centennial, Poirier recalled a harrowing story from a 106-year-old relative who miraculously survived the Halifax Explosion and still lives in the city's west end.

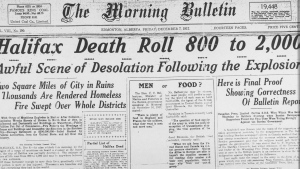

Poirier said her husband's great aunt, Halifax resident Hazel Forrest, was staying with her sister in a home on Bilby Street on Dec. 6, 1917, when two wartime ships collided in the harbour, sparking a massive explosion that killed almost 2,000 people, wounded 9,000 and left 25,000 homeless.

It was the world's largest human-made blast until an atomic bomb was detonated in 1945.

As a white-hot shock wave rolled up from the harbour, razing much of the city's north end, six-year-old Hazel was hurled through a crumbling wall.

"She remembers being thrown down from an upper floor into her uncle's arms because the wall and the stairs had been blown off," Poirier said Wednesday as a steady downpour pelted the hundreds of onlookers who gathered for a commemorative service at Fort Needham Memorial Park -- not far from what was ground zero in 1917.

"Her sister Evelyn had been bathing their baby brother, and she was thrown down the cellar stairs. The baby was scalded because they were near the stove. They found that baby across the street."

Forrest, one of the oldest survivors of the explosion, now lives in a nursing home and was unable to attend the ceremony because of blustery weather.

Halifax Mayor Mike Savage told the crowd it's the heart-rending stories of individual Haligonians that help Canadians understand an otherwise incomprehensible tragedy.

To make his point, Savage singled out the Jackson family, represented by several relatives in the crowd, which lost more than 40 members to the explosion and ensuing conflagration.

"To whomever you seek comfort from, to whomever you pray to in the evening ... when you close your eyes tonight, ask for a blessing for those who lived 100 years ago -- for those who were killed, for those who survived and to those who rebuilt," the mayor said as gusts of wind blew the rain sideways.

"We say to them what we say to our great military heroes on Remembrance Day: 'We will remember them."'

In a heated tent near the park's Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower, 82-year-old Gerald Edward Jackson recalled how his father was trapped in the rubble of a house for three days before a searcher with a dog found him.

"He was blown down into the basement of the house and the house caved in on top of him, and it was burning," he said as family members leaned in to hear the story. "It was a chaotic thing ... My dad never spoke about the explosion at all."

As the ceremony began at 9:04 a.m. -- the exact time of the blast -- a cannon was fired at the Halifax Citadel National Historic Site, and ships in the harbour sounded their horns, the mournful wail echoing across the city as the crowd observed a moment of silence.

Halifax's poet laureate, Rebecca Thomas, said most historical accounts of the explosion fail to recognize the shabby way the city's black and Indigenous populations were treated after the disaster.

"Nostalgia can sometimes be toxic and ... many voices often disappear into the past without ever being heard," she told the crowd.

African Nova Scotians living in the Africville neighbourhood, which was severely damaged by the explosion, were given only a fraction of the rebuilding funds offered to white Haligonians, she said. As for Turtle Grove, a Mi'kmaq village on the Dartmouth side of the harbour, it was wiped out by a tsunami created by the blast.

"Those who survived were segregated and kept out of the hospitals," Thomas said.

George Elliott Clarke, the Nova Scotia-born parliamentary poet laureate, recited a poem recalling the poignant moments leading up to the deadly detonation, including the imagined last goodbyes of children as they went off to school in the city's Richmond neighbourhood.

"Punctual salutations resonate in Richmond homes as spouses trudge to factory or menial jobs. Children troop to school and many of those cheery, kissed-cheek goodbyes will prove unknowingly final," he said, reading from a soaked page.

Clarke also remembered Vincent Coleman, the telegraph dispatcher who, "alert and alarmed, tapped out urgent, percussive Morse (code)" to warn an incoming train to stop before he died in the explosion.

Coleman's grandson, Calgary lawyer Jim Coleman, also spoke at the ceremony, recalling how earlier generations refused to talk about what happened.

After 100 years, that is changing, he said, adding that his grandfather's legacy as a hero should never be forgotten.

"He had a choice. He had a choice to stay or a choice to leave and try to save his life. We believe he made the right choice. He stayed and for that many people lived," he said.