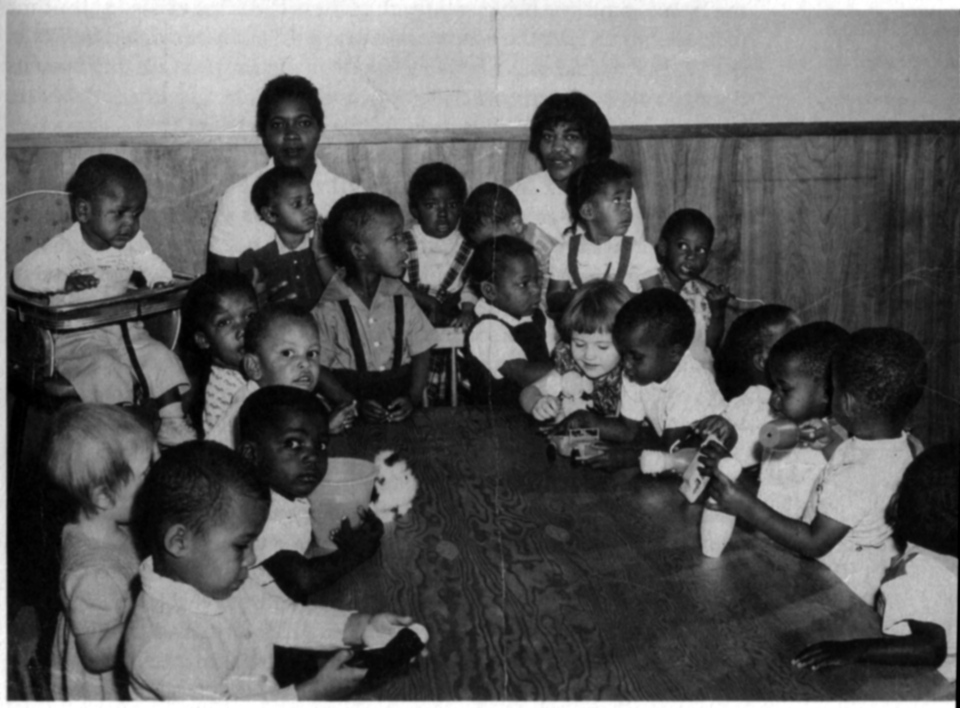

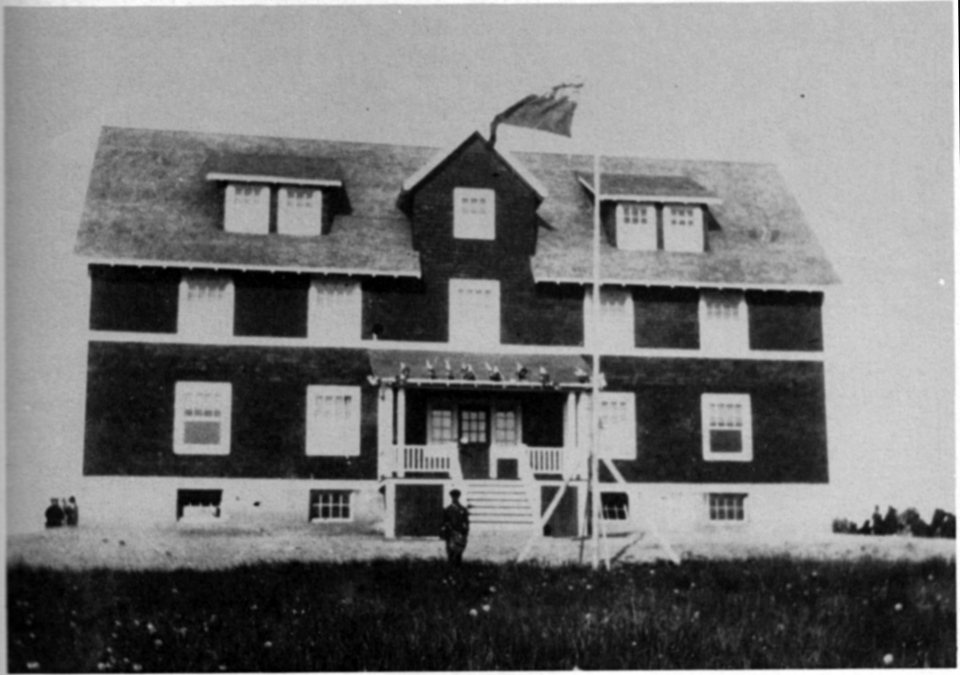

There is a flood of new complaints against the former Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children, following the airing of a CTV W5 documentary which took an in-depth look into allegations of physical and sexual abuse at the home.

One of the lawyers representing former residents of the home says he has received an influx of calls from people across the country since the episode aired on the weekend.

Former resident Tony Smith says he is pleased more people are coming forward.

“To see them finally coming out and speaking up, that’s getting back control,” he says.

Smith spent over three years at the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children in the 1990s.

He was also the first to speak out about allegations of abuse.

“We’re living with the shame and the guilt and the embarrassment that we did something wrong, and we didn’t want people to know what was happening to us,” says Smith.

“I mean, I was sexually abused by the female staff.”

Smith took part in the W5 documentary which included extensive coverage of the allegations.

About 100 former residents are now taking part in a proposed class action lawsuit against the province and the home.

Lawyer Mike Dull says his office has received about 25 calls in three days since the documentary aired, including an emotional one from the daughter of a former resident.

“She called me Monday morning after the airing of the show to let me know that her mother was watching the show that night with her, and then tearfully admitted to her that she was also a victim of abuse, and that she thought she was going to take it to her grave.”

Dull says the former residents want an apology, and the public to know what they claim happened at the home.

The allegations have prompted calls for a public inquiry, but the Nova Scotia government says there shouldn’t be one, as long as a civil suit and criminal investigation are underway.

“It does seem to me like the classic kind of a case, where a public inquiry would serve a useful purpose,” says Dalhousie Law professor Wayne MacKay.

MacKay says there are challenges in making sure people’s rights are protected if an inquiry is held during civil or criminal proceedings, but it can, and has, been done.

As for the timing, MacKay says it’s tricky because the allegations are dated.

“It may be that waiting a bit longer may not be a big issue. On the other side, the downside of waiting is some people are old enough that people are dying, or witnesses are no longer available, or some of the alleged perpetrators are no longer around.”

Still, Smith is holding out hope for a public inquiry. He says an inquiry isn’t about blame – it’s about taking a broader look at what happened, and at what can be done to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

“They have a choice that they can or don’t, and by them not, it’s looking bad for them.”

With files from CTV Atlantic's Jacqueline Foster