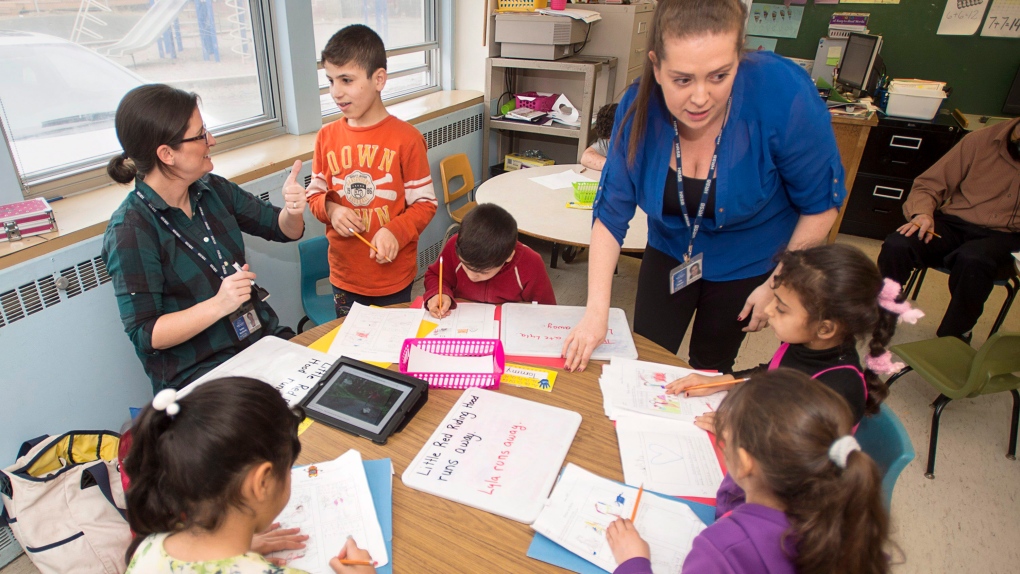

HALIFAX -- In a bustling classroom filled with streams of Arabic and English, two brothers are studies in concentration as they write out the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood.

Ahmad, 10, and Mohamad Al Marrach, 9, are among 41 Syrian children who arrived at Joseph Howe Elementary School in February, suddenly expanding the small, inner-city school's population by a third from its existing 146 students.

The bright, colourful classroom -- its name was recently added in Arabic on the door -- is the end of a long journey for the brothers. They recall moving quickly with their parents when bombs started falling on their town, and prefer their new school to one that occasionally lost power in Lebanon.

Now, they and their fellow refugees face a fresh set of challenges, including complete and sudden immersion in an unknown language. It has created demands on the school system that teachers' unions and school boards say should draw added funding from provincial and federal governments.

Julie Jebailey, the school's only Arabic-speaking teacher, translates as Mohamad talks about his new life. "Sometimes English is hard," he says.

Like most of the Syrian children in this class, which has gone from 17 to 24 kids in a few weeks, he's still at the stage of using smiles, gestures and a single word to communicate his needs.

Across the country, schools are accepting thousands of refugee children who are grappling with a new language and, in some instances, attending school for the first time after leaving camps in the Middle East.

Shelley Morse, the president of the Nova Scotia Teachers Union, says with 316 Syrians expected in the Halifax board's schools this year, she's hearing from teachers who are struggling.

"What we've been hearing is the teachers are working really hard to ensure a good transition, but the problem is the resources and funding aren't necessarily in place for that," she said in an interview.

Melinda Daye, the chair of the Halifax school board, said schools are just beginning to discover the kinds of needs the children may require, ranging from teacher assistants to speech language pathologists.

"It can't be absorbed within existing budgets. We need help," she said, adding she's put the request in to the province and hopes to hear back by June.

At Joseph Howe school, the Grade 1 and 2 class where the Al Marrach boys are immersed has seen a rapid transition.

"I can get along. It was a hard transition at first," says classroom teacher Kimberly Sparks, as she takes a brief break from teaching her existing, younger students basic literacy skills, while Jebailey and Shelley Manthorne, an English-as-an-Additional-Language teacher, work with the Syrians.

However, Manthorne and Jebailey have to move between classrooms, and often Sparks' main assistance comes from Arabic-speaking volunteers.

Another teacher at the school, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said she would prefer a system like Alberta's, where students are first given literacy programs in a separate program to prepare to enter the mainstream.

"As a language teacher myself I know it takes up to a year to catch up ... but I don't know if we have the resources to do that," said the teacher.

Joy Bowen-Eyre, the chair of the Calgary Board of Education, says the funding is a national issue -- and she recently called on Ottawa to start providing money to Alberta to help with educating the children among the 25,000 Syrians that have been brought to Canada.

She says the 427 new Syrian students in her board require funding roughly equivalent to one new school, and so far the board is covering all costs.

"We haven't had any funding at all to support the Syrian students ... That's a considerable concern for us. These are students who need significant amounts of care and support," she said.

Asked about the issue during a recent visit to Calgary, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was non-commital about what Ottawa can do.

"We're engaged constantly with partners at different levels and looking for solutions for the challenges that exist," he told reporters.

Alberta Minister of Education David Eggen said in an email his government has restored grants for English language education, and "these students may qualify for the English as a Second Language Grant if they need additional English language supports."

The federal Immigration Department didn't provide a comment by deadline.

Doug Hadley, a spokesman for the Halifax school board, said most of the roughly 316 Syrian children are spread around 30 schools and in many instances it means an addition of two or three children to a class -- not enough for the hiring of a new teacher.

However, he said the board is keeping track of the costs and the need for resources and will pass it along to the province.

A spokesperson for the Nova Scotia government declined comment on what assistance will be provided to schools.

At Joseph Howe school, Sparks said she's started a checklist each day to ensure she's spending time with each child and keeping track of their needs.

"It's busy. It is busy," she said, "but I enjoy coming in every day."