HALIFAX -- A culture of silence and shame allowed the abuse of orphans to persist for decades at the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children, according to a new report that calls for a province-wide reckoning with the historic legacy of systemic racism.

The second report by the public inquiry into abuses at the Halifax-area orphanage said former residents felt abandoned by the systems designed to protect them, allowing the abuse to go unchecked and unreported.

"Many residents felt the stigma of being `Home children' followed them at school and in the broader community," the 17-page report released Friday said. "They believe that teachers and educators who noticed their health or behaviour issues, and police who regularly returned runaways to the Home, also knew to some degree that things were not right at the Home."

Former residents described the trauma of entering care, with police and social workers telling them they were "just going for a drive" or "going to the store" before dropping them off without explanation at the orphanage, the report said.

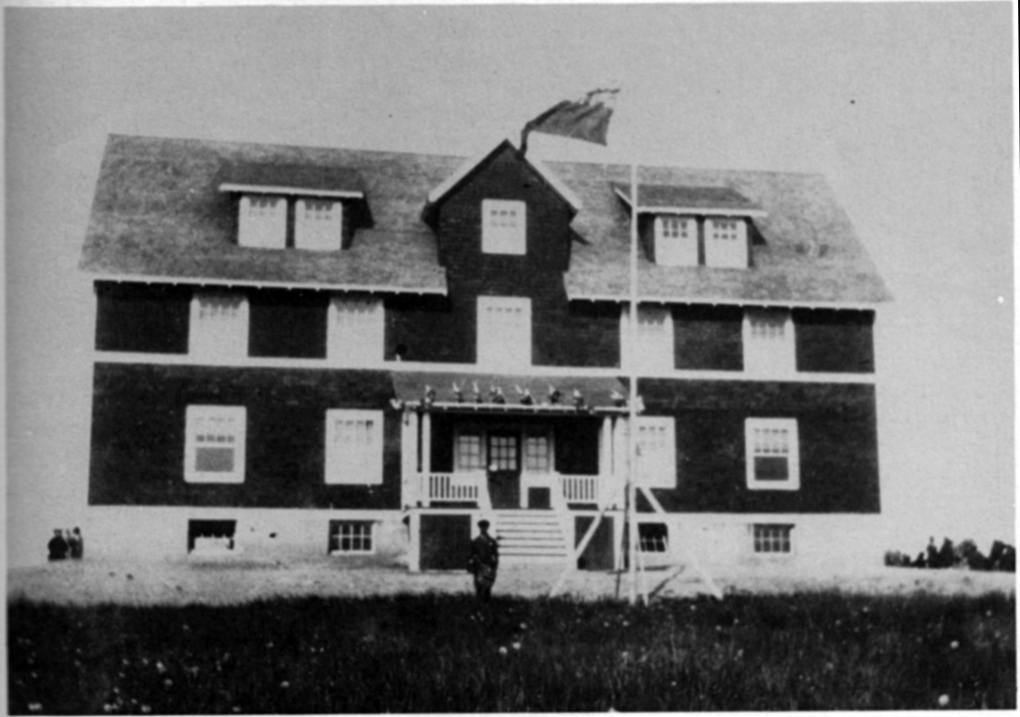

They also said they felt a sense of helplessness at the orphanage, which opened in 1921.

Some staff members pitted residents against each other and forced children to fight their friends, damaging bonds and increasing feelings of isolation, the inquiry found.

Check-ins from social workers were rare, and almost never conducted without the presence of an orphanage worker, residents told the inquiry.

"Residents felt they had no safe outlet to tell anyone what they were experiencing without fear of further harm," the report said. They felt like the adults in their lives "turned a blind eye toward their suffering."

The report by the restorative inquiry, made up of former residents, community members and the government, was released by inquiry co-chairpersons Tony Smith and Pamela Williams, chief judge of the provincial and family courts.

Launched in late 2015, the inquiry has a mandate to examine the experience of former residents of the Halifax orphanage, and systemic discrimination and racism throughout the province.

The restorative approach of the inquiry has garnered significant national and international attention, said Jennifer Llewellyn, a professor at Dalhousie University's Schulich School of Law.

"This is a novel approach to a commission of inquiry," she said, noting it was the first restorative approach to a public inquiry.

Rather than subpoena witnesses to testify before a judge, for example, the inquiry invites people to tell their stories using "sharing circles."

"This is a process that is very different," explained Williams, noting that a traditional public inquiry is more formal and can leave participants feeling uncomfortable and targeted.

The restorative approach, however, aims to set participants at ease, she said.

"People share the responsibility, come together, talk about the issues, and problem-solve," Williams said. "That kind of atmosphere invites people to be honest and to be accountable."

The approach does appear to require more time, however. The inquiry has made a request to the province to extend its original mandate from this spring to March 2019, noting that it will require additional time to prepare a comprehensive "plan for action." Its budget is expected to remain at $5 million.

In 2014, Premier Stephen McNeil formally apologized to former residents of the orphanage who say they were subjected to physical, psychological and sexual abuse over several decades up until the 1980s. Class-action lawsuits launched by former residents against the home and the provincial government ended in settlements totalling $34 million.

Smith, a former resident of the home, began telling his story nearly two decades ago.

"There was pain, suffering and anxiety, but slowly people started to find their voice," he said. "No longer do they live in shame or in guilt.

"There was a lot of singing, a lot of praying and a lot of crying. We all felt this shame, this guilt, about what we were subjected to, and now we're releasing it. We are not victims, we are survivors."

The inquiry's next report is expected to focus on planning and action, including examining the province's current care system and how issues identified by former residents persist today.

"Understanding and addressing historic and ongoing impacts of systemic racism on African Nova Scotians, while necessarily rooted in both past and present experiences, is a critical lens necessary to create meaningful change for the future," the report said.

Indeed, the inquiry found that racism in Nova Scotia continues to breed mistrust and sometimes even fear of public agencies.

George Gray, a community representative with the inquiry, said confronting racism in Nova Scotia has been a "long time coming."

"This is a long process. It's a journey that we have to go through," he said. "Racism has been here for a long time and we as a race of people have been marginalized, and it's not going to improve overnight."