HALIFAX -- Nova Scotia has suffered from institutional racism, Premier Stephen McNeil acknowledged Friday as the government released a report outlining its role in an inquiry into decades of abuses at a former Halifax-area orphanage.

McNeil tabled the eight-page report in the legislature, saying the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children Restorative Inquiry represents an important opportunity to address the "legacy and impact of systemic racism and inequality in our province."

"We embarked on this journey because we recognized we must do better," said McNeil. "We need to understand our past fully so that we can begin to address what to do next to ensure a better future for African Nova Scotian children and their families."

The report, by the inquiry's Reflection and Action Task Group, summarizes the actions taken by the government leading up to and after the announcement of the inquiry in June 2015.

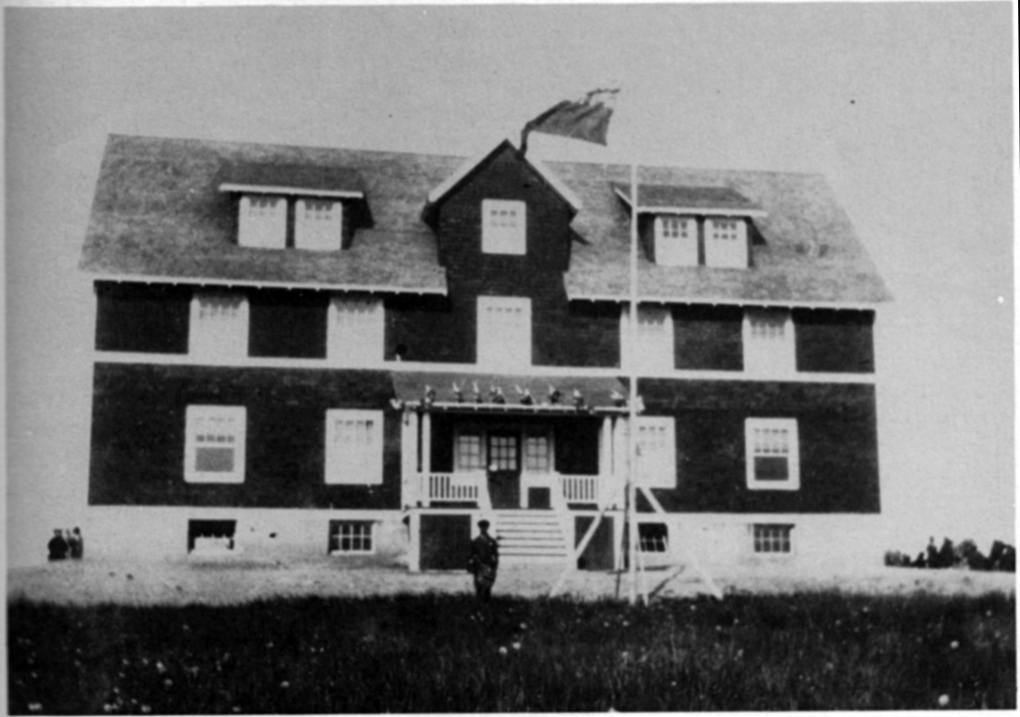

The home, which opened in 1921, was the site of alleged mistreatment and abuse from the 1940s through until the early 1980s. An RCMP investigation was eventually dropped in 2012 after police said they had difficulties corroborating the allegations of sexual and physical abuse.

The report says the government continues to help the inquiry through providing health supports for former residents of the home, and by providing administrative support and by making relevant records and information available as the inquiry conducts its work.

"Government is committed to critically examining its role in the history of the NSHCC (orphanage) as a pathway to address how the legacy of systemic and institutional racism has impacted individuals, families and communities for generations in Nova Scotia," the report states.

It says the inquiry has a mandate to examine the role government departments including health, education, justice and community services played in the "harmful history and legacy" of the NSHCC."

"I've made this very clear, there's been institutional racism in the province," McNeil told reporters.

"In order to find solutions to that the institutions have to be involved ... and I've been very proud of the way the public service has worked together."

Tony Smith, a former resident of the home and an inquiry council co-chair, said the government has been a full participant in the process as promised.

"It has been more than words. I'm a firm believer that actions speak louder than words and their actions most definitely supports the words that you hear today."

Smith said the inquiry, which was launched with a $5 million budget, will release a report later this fall, and expects to wrap up its work with a final report in about 18 months.

Prior to the inquiry, class-action lawsuits launched by the former residents against the home and the provincial government ended in settlements totalling $34 million, followed by a public apology from the premier in 2014.

Smith said part of the reason for the inquiry's slower-than-expected pace is its unique nature. It had been given a two-and-a-half-year mandate.

"This approach that we are taking -- it's not blaming, it's working together collaboratively. In order to understand why this happened in the first place we have to be in a position to have dialogue and a safe place so that everybody can contribute."

He said finishing up the settlement process played a role in putting the inquiry behind by about six months or more.

"We had to wait until those issues were dealt with so that they (former residents) felt comfortable coming in and talking," Smith said.

The inquiry's three phases include relationship building, learning and understanding, and planning and action. Currently the proceedings are in their second phase.

McNeil said the government is committed to seeing the inquiry through to the end.

"Not only will it be very powerful for Nova Scotia, I think the process that we've landed on will be replicated beyond," he said. "People beyond our province are talking to Tony (Smith) and others wanting to look at how they are doing it and trying to understand the powerful impact it's having."