HALIFAX -- The lawyer for a Halifax man at the centre of a chemical scare that led to evacuations in two cities says his client may have had enough chemicals to make 11 different types of explosives, but there's no evidence that he was interested in doing that.

Mike Taylor told Nova Scotia Supreme Court on Tuesday that his client, Christopher Phillips, is a chemist whose large collection of chemicals would be standard fare in any given laboratory.

Taylor made the comment while questioning Melanie Brochu, an RCMP forensic scientist who testified Phillips had about 500 chemicals to draw from, though she said the accused did not appear to be making any bombs when she examined hundreds of bottles and jars stored near a cottage east of Halifax.

Brochu told the court that 42 of the chemicals she examined could be used to make an explosive compound, some of them requiring the addition of a common household item like milk or cotton balls.

Taylor said Brochu's finding meant that over 90 per cent of the chemicals in Phillips's possession could not be used for such a purpose. And he stressed that virtually all of the 42 named chemicals had other uses, including as household products.

"You would find many or most (of these chemicals) in labs and there are so many chemicals that ... have many household uses," Taylor said outside court. "It goes to show that Mr. Phillips had those substances most likely for no improper purpose."

Phillips is charged with threatening police in an email to a friend and possessing a weapon -- the poisonous chemical osmium tetroxide -- for a dangerous purpose. That chemical was found in another shed near Phillips's home in the Halifax area.

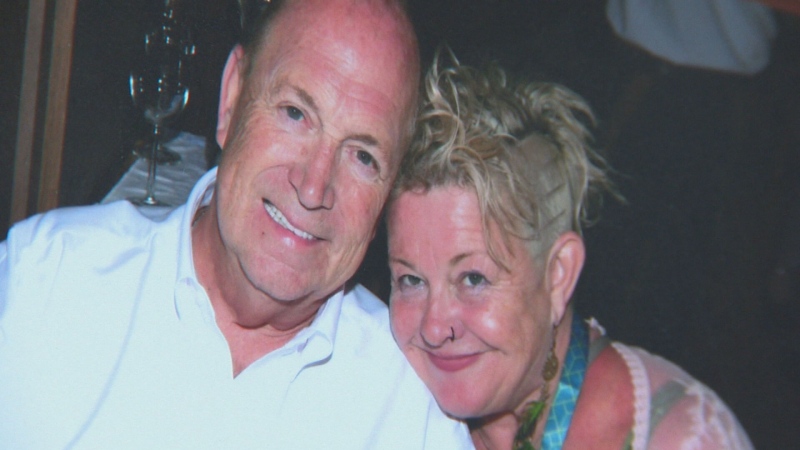

On Jan. 19, Phillips's wife told police she was worried about his mental health and that she feared for the safety of her family because he possessed a large stockpile of chemicals and was talking about enriching uranium.

Neighbourhoods in Halifax and Grand Desert, N.S., were subsequently evacuated as police moved in to search the two properties. Phillips was arrested Jan. 21 in an Ottawa hotel after it was evacuated by police. No chemicals were found there.

Brochu testified that osmium tetroxide is a toxic, corrosive chemical that can be deadly if swallowed. She said it is normally used as a biological stain when examining cells under a microscope. It also can be used as an oxidizing agent or as a fertilizer, she said.

Under questioning, she agreed when Taylor suggested she didn't have the expertise to say what would happen if a small vial of osmium tetroxide was broken in a large room with someone in it.

Earlier, the scientist told court the chemicals in the shed in Grand Desert were difficult to assess because many of the containers were labelled with an alpha-numeric code that gave no indication of what was inside.

As well, she said the chemicals in Grand Desert were stored improperly because there was inadequate ventilation and no temperature controls in the shed. None of the chemicals were accompanied by the required Material Safety Data Sheets, she said, citing standard laboratory practice.

That was also the case for the unheated shed in Cole Harbour where the osmium tetroxide was found in a box, Brochu said, adding that the chemical could have frozen and ruptured the ampules it was in.

When Taylor asked if Brochu was aware of a law that required hobby chemists to have safety data sheets on hand, she said she was only speaking about accredited federal labs.

Phillips has not been charged with improper storage of chemicals. Taylor has stressed that his client purchased the osmium tetroxide legally, and that he had far less than the legal limit in his possession -- 230 millilitres in liquid form and 31 grams in solid form.

At an earlier bail hearing, which was not covered by a standard publication ban, Phillips testified that he owned the chemicals to extract heavy metals and was running a chemical business.