HALIFAX -- The crime-fighting potential of police street checks must be weighed against the possible negative impact on racialized communities, says an independent expert examining the practice in Halifax.

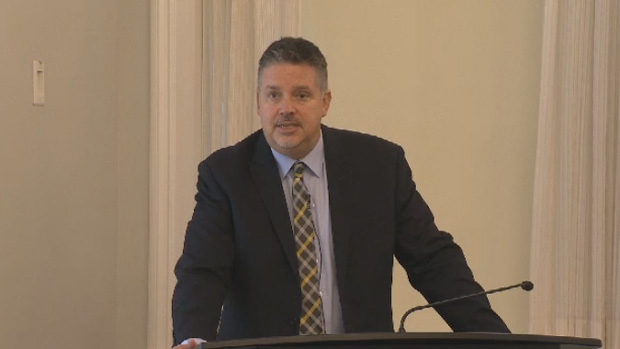

"It might be a double-edged sword," Scot Wortley told a board of police commissioners meeting Monday. "Street checks have potentially very detrimental impacts on certain populations and we've got to weigh those consequences with the possible crime-fighting potential."

The Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission has hired Wortley, a University of Toronto criminology professor and author on race and crime, to review street checks in Halifax after data showed black men were three times more likely than whites to be subjected to the controversial practice.

Advocates of police street checks say it helps law enforcement gather intelligence and improve public safety, while opponents say it targets black people and violates human rights.

Halifax police say street checks are used to record suspicious activity. Although police stop and question people, the checks can also be "passive" with information recorded based on observations rather than interactions.

"This is by no means a problem that is isolated to Halifax," Wortley said. "The issue of policing and how different minority communities are policed is probably one of the most contentious and controversial issues in law enforcement."

Wortley will conduct a detailed analysis of street check data, hold town hall-style meetings in the community, identify gaps in the data, evaluate the potential for racial bias and make recommendations.

He said a final report should be ready in about two months.

"I think the issue is determining what proportion of that overrepresentation (of black people in street check data) is potentially due to bias and what proportion is due to what might be called legitimate police activities," Wortley said.

He said he first became aware of racially-biased policing in Nova Scotia after a human rights inquiry in 2003 found police discriminated against Kirk Johnson.

The former professional boxer claimed during the inquiry that Halifax police stopped his car dozens of times over a five-year period because of racial profiling.

"The issue of racially-biased policing has existed for a long time," Wortley said. "We've historically had a lot of denial ... we go through a crisis cycle where the issue will disappear for a few years and then there will be a shooting or an event captured on video that creates the entire crisis again."

However, he said that it's starting to change as provinces like Ontario become more open to collecting race-based data.

"For many years in Ontario, the mantra from law enforcement was this is not a problem, this is not an issue, these are unfounded allegations," said Wortley, who has worked with the Ontario government's Anti-Racism Directorate to develop standards for the collection and dissemination of race-based data within the public sector.

"The release of data now has made a difference at the policy level because it's harder to ignore the realities."

Earlier this year, Ontario banned police carding, a controversial practice also known as street checks.

However, Halifax Regional Police Chief Jean-Michel Blais said the street checks conducted in Halifax differ from carding.

"Carding is a totally different thing. It's based on a geographical area," he said. "Carding is something that really we just don't do."

Still, Blais acknowledged that "there are community members who view the interactions with police as being less than optimal."