For nearly two weeks I have been explaining the concept of human rights reporting to journalists at Citizen TV (CTV) here in Juba. When one of them tells me he wants to do a story about “gender-based violence” I realize we must first deal with another issue: how to focus and pitch a doable story. I decide to hold a workshop.

I ask the reporter what specifically he is interested in. He tells the group he wants to cover “honour marriage,” the act of forcing a young girl to marry in exchange for money.

I have been telling the journalists about the need to find everyday people to be characters in our stories instead of just interviewing officials. But as I’m asking more questions, looking to further narrow our focus, we realize our great character is sitting in the room.

Human rights stories are closer than we think.

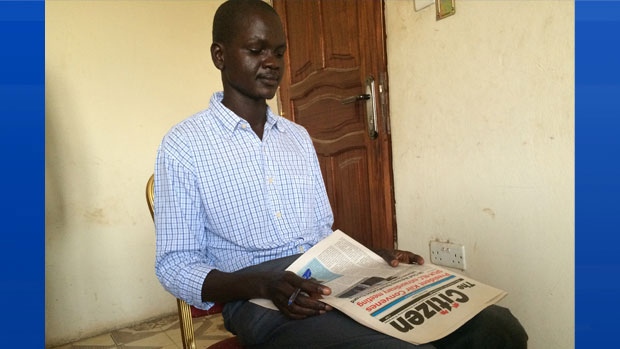

Arou David is a young journalist with a compelling story of his own. He speaks up to say he has firsthand experience with honour marriage.

In October, a South Sudanese man now living in Australia came home and asked for his sister’s hand.

At 17, she declined, saying she wasn’t ready for marriage and is still in school. The man didn’t listen, and went to the girl’s father.

“Because Dad needs some wealth, he accepted,” says Arou David.

He tried to convince the man to wait, tried to convince his father not to force his sister. Nothing worked. The marriage was to proceed.

But in an unprecedented, and even taboo, move in South Sudanese culture, Arou David took his own father to court.

“To me, I think this is against human rights,” he says. “It’s a broad human rights violation… Even according to the Constitution of South Sudan a person who is below the age of 18 cannot be married because she is still a child.”

The siblings’ father eventually gave up the court battle, but it was not without cost.

“He has disowned us because of that issue,” says Arou David. “The relationship is broken. We don’t even communicate.”

Arou David and his brother now do what they can to provide for their sister and pay for her school fees. Even distant relatives are divided, most siding with the father. Still, for the young journalist, it’s worth it.

“I’m not fighting for myself. I was fighting for her right. To see that she completes her studies like me, to see that she gets a family of her choice, to see that her life is going well. That’s what I was fighting for.”

I asked him then how he feels about human rights reporting.

“It’s important because I want people outside to know, to come up with the voices to fight against this evil which is common in our country… It has been happening always during the time of our great grandfathers, but we don’t want it to continue like that. We want it to stop.”

The workshop ends with the two journalists discussing the possibility of working together on a story. With such strong voices illustrating the possibility for change, their story could be the beginning of the end of the evil of which they speak.