The recent escape of a convicted killer from Dorchester Penitentiary has residents in the area speaking out about prison security.

A 24-hour man hunt ensued after Steven Bugden walked away from the minimum security facility at Dorchester Penetentiary on Feb. 7. Bugden, 45, was sentenced to life in prison for the second-degree murder of 22-year-old Angela Tong in Ottawa in 1997. His escape was described as a “walk-out” by penitentiary management.

But the situation had community members who the prisoners actually are.

“It was about 10:30, and the first thing that popped up on my Facebook was a convicted killer escaped in Dorchester,” says Deborah Jollimore, a mother of three who’s lived in Dorchester for the past 15 years.

Community members found out about Budgen's escape the morning of Feb. 8. At that point, Bugden had been on the run for at least 12 hours.

“He could have come into anybody's house,” Jollimore says. “I would have liked to have known that there was a potential for a murderer to be lose in and around my house.”

Teena Adams, who has lived in Dorchester for over two decades, says there’s been a history of residents being kept in the dark when prisoners escape.

“There's a lot of elderly people in the community. There's people with children,” says Adams. "Nobody knew nothing. He's been gone all night and half of the day. People could be out walking, kids are playing.”

Bugden was eventually recaptured 24 hours after escaping custody. He was discovered in a ravine not far from the prison he slipped away from.

This isn’t the first time a prisoner has escaped from Dorchester Penitentiary. Allan Legere used an ear infection as an excuse and a hospital bathroom as his escape route. Decades later, it was a toothache that won freedom for Jermaine Carvar, who somehow escaped his leg shackles in the back of a corrections van. Then Thomas Jones smashed the back window of this sheriff’s van. And Marc Pellerin contorted his hands, got out of his cuffs and ran out of the van while being transferred.

There have been 22 escaped prisoner situations in the last decade from the federal facilities in this region.

“Occasionally people do walk away from these institutions because in some cases there are no walls,” says criminologist Michael Boudreau. “In any given year there are a handful, but not something that I think is a significant threat to public safety.”

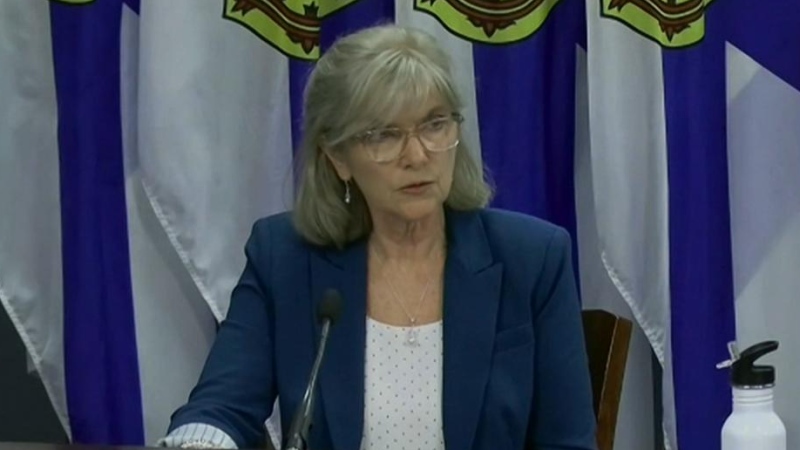

The Nova Scotia General Employees Union says when escapes do happen, the province is reactionary.

“Why aren't they proactive? I'm still trying to answer that question,” NSGEU president Jason MacLean says.

MacLean was a correctional officer for 22 years. He says not all requests in follow-up reports are implemented.

“What we need is implementation because we always run up against the cost factor,” MacLean says. “I don't believe that public safety should be measured on how much it costs.”

But there are more boots on the ground. The Department of Justice confirms it's hired 40 additional sheriffs in the province since last year.

There was a recommendation for sheriffs to be equipped with firearms, but the department instead opted for Tasers. The province also confirms that it's sheriffs vans are being overhauled to allow for better surveillance of prisoners.

“There's always more that can be done in terms of evaluating practices within the facilities,” Michael Boudreau says. “Some would argue that perhaps there's a need for more guards within the institutions. Sometimes that would work, sometimes not. But for the most part the system is working effectively.”

But for the people who live in these communities, it doesn’t matter if it's a big pen or a little pen prisoners escape from. For them, there is no acceptable level of risk.

“We know nothing, absolutely nothing about this. Crazy, just crazy,” says Teena Adams.

Residents say even one escape is one too many.

With files from CTV Atlantic’s Laura Brown.