A Halifax doctor is working on high tech solutions to treating hearing loss.

Dr. Manohar Bance is an otolaryngologist at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax.

His lab is working on new technology to better see the middle and inner ear.

Many of the structures in the ear are microscopic and can be difficult to spot on CT scans and MRIs. Better imaging would allow doctors to determine the causes of hearing loss, and help make cochlear implants even more effective.

“It may mean that we understand why cochlear implants work better or work worse in some patients, so we can understand how to design a better cochlear implant, what it does when it goes in, what path it takes, how it tears normal structures, we can design better shaped ones,” says Bance.

Cochlear implants are used when the inner ear is damaged. The electronic device does the work of the cochlea (the part of the ear that translates sound into nerve impulses) to provide sound signals to the brain.

“There's a coil and the coil transmits across the skin to a coil that's implanted,” says Bance. “So that takes the power and the electro impulses and it stimulates the electrodes that are wrapped around the nerve of hearing inside the cochlea.”

Bance says the implant has different components that respond to various tones and frequencies, just like a normal ear.

“This does the same thing electrically. It puts the high tones in one part of the cochlea and low tones in another part of the cochlea. So the nerve gets stimulated and sends messages directly to the ear.”

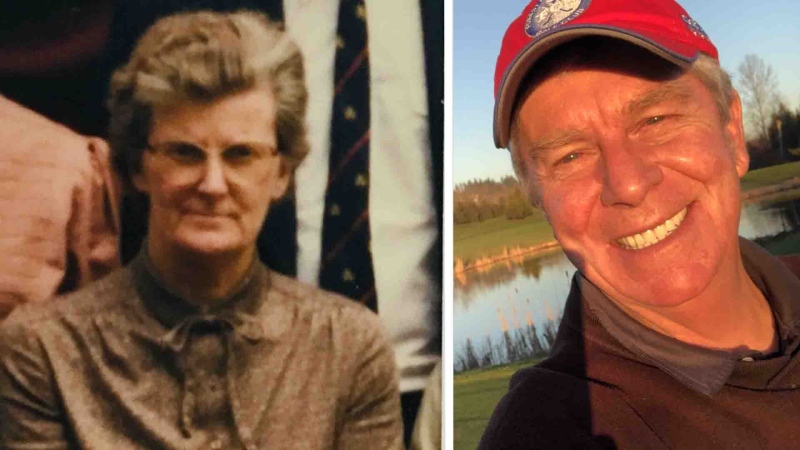

Gary Dunbrack, 64, received a cochlear implant in 2012.

He first began to have hearing issues about 40 years ago.

“In the 70s, I had a fullness in the ear and my hearing was dropping. It progressively got worse. Then I had dizzy spells in the early 80s, which really proved it was Ménière's disease,” says Dunbrack.

By the early 90s, his hearing had diminished even further.

“I more or less withdrew from a lot of activities, like going to Neptune for example, because I couldn't hear, going to a theatre to watch a show, I didn't go. I hated to go to social functions,” says Dunbrack.

After years of relying on hearing aids, Dunbrack got a cochlear implant in 2012. He says the procedure was life changing.

“Now it's the exact opposite. If I hear somebody, or see somebody, I really go over and to them and make a point to say hello and talk to them,” says Dunbrack. “It made all the difference in the world from then on. I was a little hesitant at first, but after a few adjustments, it works like a charm.”

Dr. Bance hopes someday patients may be able to skip the procedure all together.

“If we can figure out why people went deaf, we might develop therapies to reverse it. So you may not actually need a cochlear implant.”